7 difficult people you deal with as an Agile Delivery Lead

And how Delivery Leads handle them without losing their mind

When I was a Scrum Master, my biggest headache was the senior developer who rolled his eyes every time I said "Sprint Goal."

I spent my days protecting the very people who wanted me out.

It's silly… really!

Agile Delivery Leads don’t deal with all this, but that doesn’t mean their lives are free of problematic personalities.

They (often) get steamrolled by VPs who don’t care about "story points" or "team feelings.” They just want to know why we are not done yet.

The ecosystem you’re in is complex, and as a Delivery Lead, you’re responsible for managing delivery across this complexity.

For you, the "difficult people" are not resistant team members. They are executives, gatekeepers, and ghosts from the PMO.

In this post, I will show you the reality of the 7 difficult personalities I encountered and how I handled them without losing my mind.

Let’s get started.

Got an urgent question?

Get a quick answer by joining the subscriber chat below.

#1: Manager who needs control

Why are they “difficult”?

They’re NOT “against Agile.” No! They (usually) love Agility.

The problem with a control-oriented manager is that they simply have a “high” need for Certainty.

They’re usually accountable for outcomes, and if they don’t trust the delivery system to hold up under pressure, they step in and try to manage the work directly.

You’ll notice it when they keep telling the team how to do the work instead of aligning on what outcomes are needed. They sometimes even override priorities, interrupt sprints, and assign work directly to individuals. They also sometimes hold status meetings for compliance checks.

What I’ve found works best with them is not fighting them on “control vs autonomy.”

No. You’ll burn yourself out if you do that.

Agree on a few things with them:

clear guardrails that give them confidence in the delivery (eg, incident SLAs, escalation thresholds, reporting cadence, etc.)

a predictable visibility cadence (eg, weekly delivery review, dependency view, risk log, forecast updates)

Also, make decision-making clear, i.e. who sets priorities, who decides on implementation, and under what conditions work can be interrupted.

Once they can see that you’re delivering reliably and consistently, they usually stop grabbing the steering wheel.

#2: HiPPO Stakeholder

HiPPOs like to be the decision makers. And they don’t trust data, experiments, the way you do.

You will hear them saying,

“I don’t care what research says. Customers want this.”

You can’t fight their authority, so that’s out of the question.

The only way out is to make them feel safe to be data-informed.

When I’m working with a HiPPO, I bring options with clear tradeoffs so it doesn’t feel like I’m challenging their authority.

For example,

Let’s say your HiPPO says, “We need Feature X. Customers want this.”

I won’t debate that.

I’ll respond by offering a list of options like:

Option A (fast, risky): Build the full feature now to hit the date, with limited validation and a higher chance we’ll need to rework it

Option B (slower, safer): Spend time validating first, then build. This will have lower rework risk, but we accept a later delivery

Option C (MVP): Deliver the smallest usable version to test the outcome quickly, then decide whether to scale it up or stop

Then propose an “executive-friendly” experiment:

“Let’s run a 2-week experiment. We’ll ship a thin slice to a small segment and agree up front what ‘worked’ looks like.”

Timebox: 2 weeks

Success metrics (agreed with them):

At least +10% increase in the target conversion step

No more than +2% increase in support tickets related to this

Put it in a decision log and email it to them. For example:

Decision: Proceed with Option C (thin slice) of Feature X for a 2-week experiment to a limited audience.

Assumptions: Customers want Feature X enough that it will improve the target conversion step without increasing support load.

Expected impact: +10% on the target conversion step; support tickets stay within +2%.

Review date: End of week 2 (based on the agreed metrics), show “did the assumptions hold or not?”At the end of week 2… review:

“Conversion moved +3% (below target).

Support tickets went +4% (above threshold).

Based on what we agreed, this didn’t meet the bar. Do you want to adjust the approach or stop?”

This helps them stay in charge of the decision while slowly learning to trust evidence over instinct because it was their experiment, their options, and their success criteria all along.

#3: Product Owner who wants Everything

For them, “Everything Is Priority #1.”

It’s not their fault, though!

They’re usually hammered by multiple stakeholders, all shouting that their thing is urgent. For them, prioritization may mean saying “no” to important people, which they want to avoid… at any cost!

As a result, they:

Bloat and constantly reshuffle backlogs

Have no clear product goal

Want the team to “keep delivering”

What I’ve found works with them is:

1) Bringing the conversation back to capacity and tradeoffs. Use capacity as a forcing function:

“We’ve got roughly XXX engineer-days (or XX points) this sprint. What outcome will realistically fit in?”

2) You can also reinforce priority. If something is moving up, something else must move down.

3) I also try to shift their focus to measurable outcomes, such as conversions or cost reduction, and not just “features shipped.”

This gently pulls them out of “everything is urgent” mode into a shared picture of what really matters “now.”

#4: Stakeholder who wants to Avoid Risks

These are worse than a HiPPO.

You’ll find this person difficult because they might disagree but not feel safe saying it out loud.

So you get that frustrating pattern where a meeting ends in “agreement,” and then… nothing happens.

They don’t respond, approvals don’t happen, decisions get quietly reopened weeks later, and you find out they’ve escalated sideways to someone else to slow things down.

What I’ve found works is:

1) To take the heat out of the public forum and surface the real concern privately in a 1:1. A short 1:1 is often where you finally hear what’s going on. It may be risk, reputation, workload, loss of control, or even competing priorities.

2) Asking for clear consent so no one is operating on a vague “sure.”

For example:

“Are you a yes, a no, or a yes-with-conditions?”

If it’s conditional, turn it into something concrete: “What specifically would make this easy for you to support?”

Then document and confirm the decision, the owner, and the date in short written follow-ups, so there’s less room for misinterpretation later.

This turns vague, silent resistance into clear, owned commitments so we’re no longer guessing where things stand, and they can say “yes” (or “not yet”) without feeling exposed.

#5: Resource Controller

Resource controllers are accountable for utilization and staffing. You’re accountable for delivery and outcomes.

So your incentives… collide.

Have you seen instances where people are pulled into multiple initiatives, teams are frequently reshuffled, and key skills are temporarily 'borrowed,' leading to hidden delays?

Yep… resource controllers are the ones responsible.

When I’m working with a resource manager, I don’t argue.

I work strategically:

I quantify the cost of context switching using impacts on lead times and missed dates

II negotiate for “somewhat” stable teams with explicit allocation because even a 70/30 split is better than “everyone everywhere.”

I also create a simple dependency/capacity map so the tradeoffs are visible at a leadership level

And if we absolutely can’t have a skill full-time and we really do need to “borrow” someone, I propose a clear loan agreement with duration, purpose, expected outcomes, and a return date

For example:

“Yes, we want to borrow Sam. Let’s make the agreement clear so we don’t accidentally break the team’s flow. Sam joins our team for 2 weeks to unblock the payment integration. The expected outcome is a working integration in staging, plus a short handover note so the team can support it. Sam is back with you on Monday, the 15th. If we’re not on track by the end of week 1, you and I can decide whether we extend or de-scope.”

This turns the tug-of-war over “resources” into a visible, time-bound agreement that can be renegotiated… if needed.

#6: Compliance Gatekeeper

This person says “no” by default.

They’re incentivized to prevent bad outcomes, not to enable good ones, and they may be burned by past failures.

Take Security or Legal, for example. They usually get pulled in too late.

So there are late approvals, heavy documentation, etc., because they want to tick every checkbox in the compliance checklist.

When I’m working with a risk/compliance gatekeeper:

1) I bring them in early with a clear role: “Help us design the safe path.” They help the team shape the approach rather than gatekeeping at the end

2) I also encourage the team toward automated controls. Things like policy-as-code and pipeline checks with automated evidence so compliance isn’t manual and it is quick.

For example:

“Instead of a release checklist where someone manually confirms security items, I ask the team to turn those items into pipeline gates. For example, every pull request automatically runs dependency scanning and a vulnerability check. If it finds a critical issue, the build fails, and we fix it before merging. When it passes, the pipeline automatically stores the scan report and approver record, so the ‘evidence’ is generated as part of delivery. Not chased at the end.”

3) Also, because they usually default to “no,” I ask them for a conditional “yes.” Conditional yes works in most cases.

Example:

I ask, “Under what conditions would this be approved?”

And they might respond with conditions like:

“If customer data is encrypted”

“If access is limited to specific roles and we have an audit trail”

“If we run a security scan and fix any critical findings”

“If we have a rollback plan and monitoring in place”

The team reflects on these conditions and prepares a deliverable checklist.

“So if we implement…

encryption,

role-based access, audit logging,

run the scan and clear criticals, and

add rollback + monitoring,

… you’ll approve? “

So instead of racing to satisfy a mysterious checklist at the end, the team builds their conditions into the work from the start.

This earns them a predictable “yes.”

#7: Sponsor who is Always Absent

Disengaged Sponsors want results but won’t show up. They hold the authority you need for decisions, but they’re… ABSENT.

So… decisions are delayed. The team ends up guessing. And when you try to escalate, it goes nowhere.

When I’m dealing with a disengaged sponsor, I stop requesting long meetings (that they won’t attend anyway). I ask for short, focused slots where they can make a few specific calls that unblock delivery.

Example:

“Can I get 15 minutes with you tomorrow? I need three decisions to unblock the team:

Decision 1: Do we go with Option A or Option B for the release approach?

Decision 2: Are we prioritizing X over Y this sprint?

Decision 3…

Look, I get it.

They are busy, and this makes it easier for them to do their job as a sponsor. I get the decisions I need, and they get progress without feeling dragged into endless meetings.

Bottomline…

Here’s a suggestion.

As an Agile Delivery Lead, it's most helpful to remember to check the system first, rather than jumping to conclusions about individuals. This way, you approach challenges with a more collaborative mindset.

When someone feels “difficult,” run a quick diagnostic:

Is their behaviour rational given their incentives?

Do they have a different definition of success?

Are we asking them to take risks without visibility?

Is there an unspoken fear (career risk, audit risk, reputational risk)?

When you fix those conditions, many “difficult people” stop being difficult.

Also… don’t wait until there’s a problem.

Build alliances early through 1:1s with key stakeholders and by delivering small wins that matter to THEM.

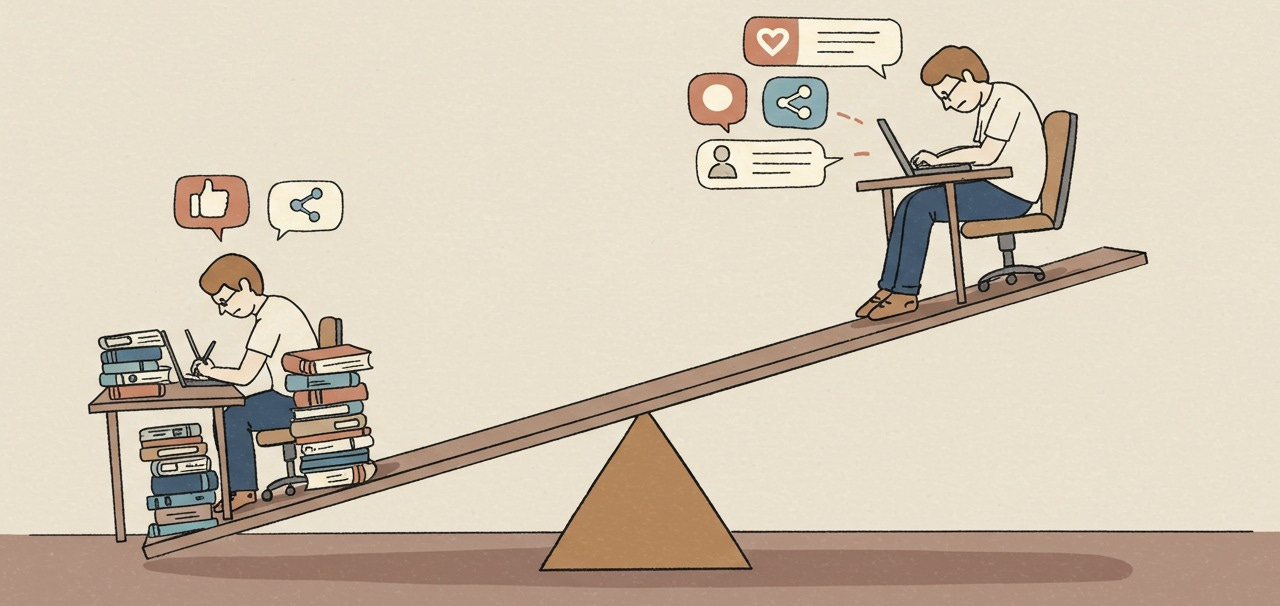

As a Scrum Masters you asked, “How do I coach the team better so they can succeed?”

As an Agile Delivery Lead, you ask, “How do I make the organization better for teams to succeed in?”

Also…

When you look at it this way, you realize that your hardest “people” are usually the ones closest to power, budgets, approvals, and competing priorities.

And that’s exactly where your leverage lies.

Show your support

Every post on Winning Strategy takes a few days of research and 1 full day of writing. You can show your support with small gestures.

Liked this post? Make sure to 💙 click the like button.

Feedback or addition? Make sure to 💬 comment.

Know someone who would find this helpful? Make sure to recommend it.

I strongly advise that you download and use the Substack app. This will allow you to access our community chat, where you can get your questions answered and your doubts cleared promptly.

Further Reading

13 Techniques to Handle Difficult Situations During Meetings with Ease

Why some Product Owners are Harder to Work With than Others?

Connect With Me

Winning Strategy provides insights from my experiences at Twitter, Amazon, and my current role as an Executive Product Coach at one of North America’s largest banks.

Solid breakdown of how incentive structures create most stakeholder friction. The diagnostic at the end about checking systmes before labeling people is the real move. I've noticed that alot of resistance dissolves once you align on visible tradeoffs rather than abstract principles. Treating every conflict as a coordination problem first saves so much wasted energy.