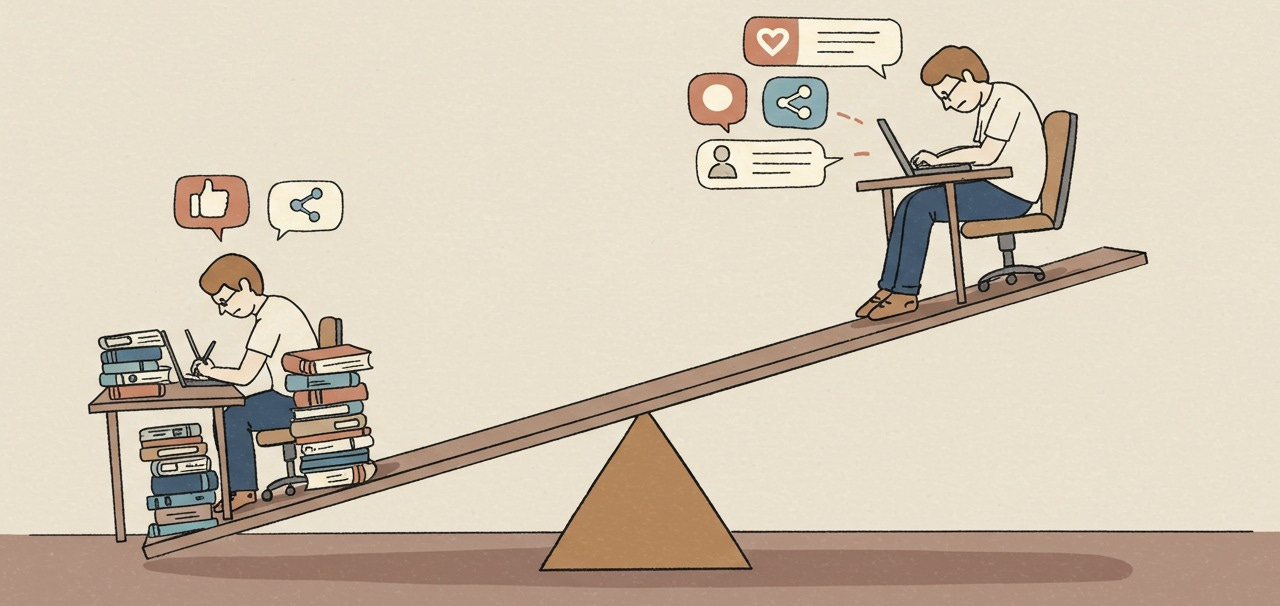

Autonomy vs Commitment

How to help your teams balance individual autonomy with team commitment

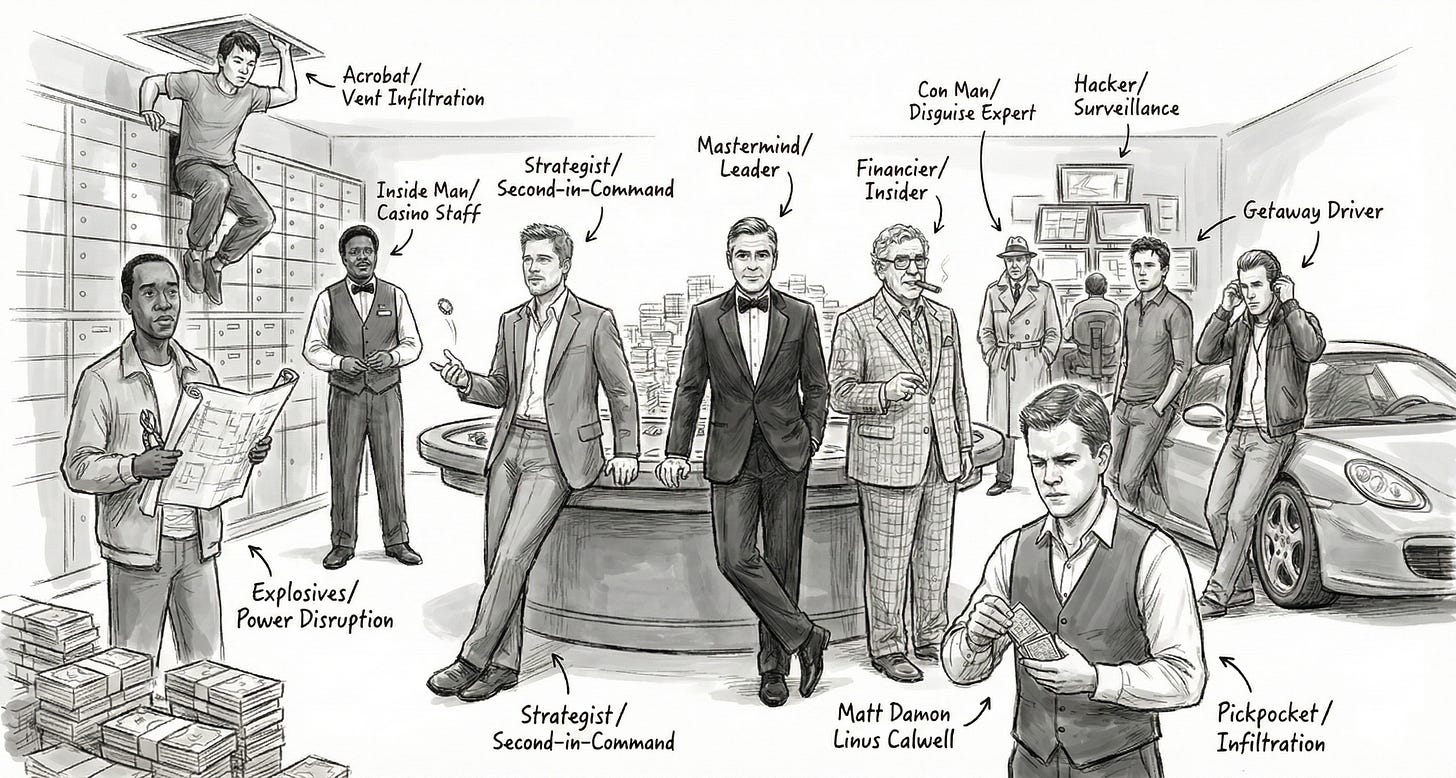

Have you watched Ocean’s Eleven? The movie?

Not the 1960 Sinatra version, the 2001 Soderbergh version, the one where George Clooney assembles a team of eleven specialists to rob three Las Vegas casinos simultaneously.

Here’s what’s special about that team.

Every single person on the team is expertly good at their specific thing. Basher is the explosives guy. Livingston handles surveillance. Linus is the pickpocket. They each operate with near total autonomy within their domain. Nobody tells Basher how to rig a charge, or gives Livingston direction on hacking cameras.

They all have “autonomy,” but at the same time, they're all “committed” to ONE SINGLE PLAN.

One shared commitment and one timeline. If Basher misuses his freedom and blows the vault thirty seconds early, it doesn't matter how brilliant his (or other people’s) technique is. The whole thing collapses.

Danny Ocean (their lead) is not commanding or controlling anyone. He ensures that these eleven autonomous specialists stay aligned on a single shared outcome. He sets the target and removes obstacles. And then he gets out of the way.

Now replace this heist with "sprint delivery," replace the eleven specialists with your dev team, and replace Danny Ocean with YOU, the Delivery Lead (or the Scrum Master).

The job is almost identical with one tiny difference.

How is Danny Ocean able to make individual autonomy and team commitment coexist so easily, and why do we find it so difficult?

Let me explain why and, more importantly, what the research says about how to actually do it.

Let’s dig in.

Got an urgent question?

Get a quick answer by joining the subscriber chat below.

Why autonomy matters

I know a ton of leaders who treat autonomy as a perk, something you grant to senior engineers who've "earned it." The research says something very different.

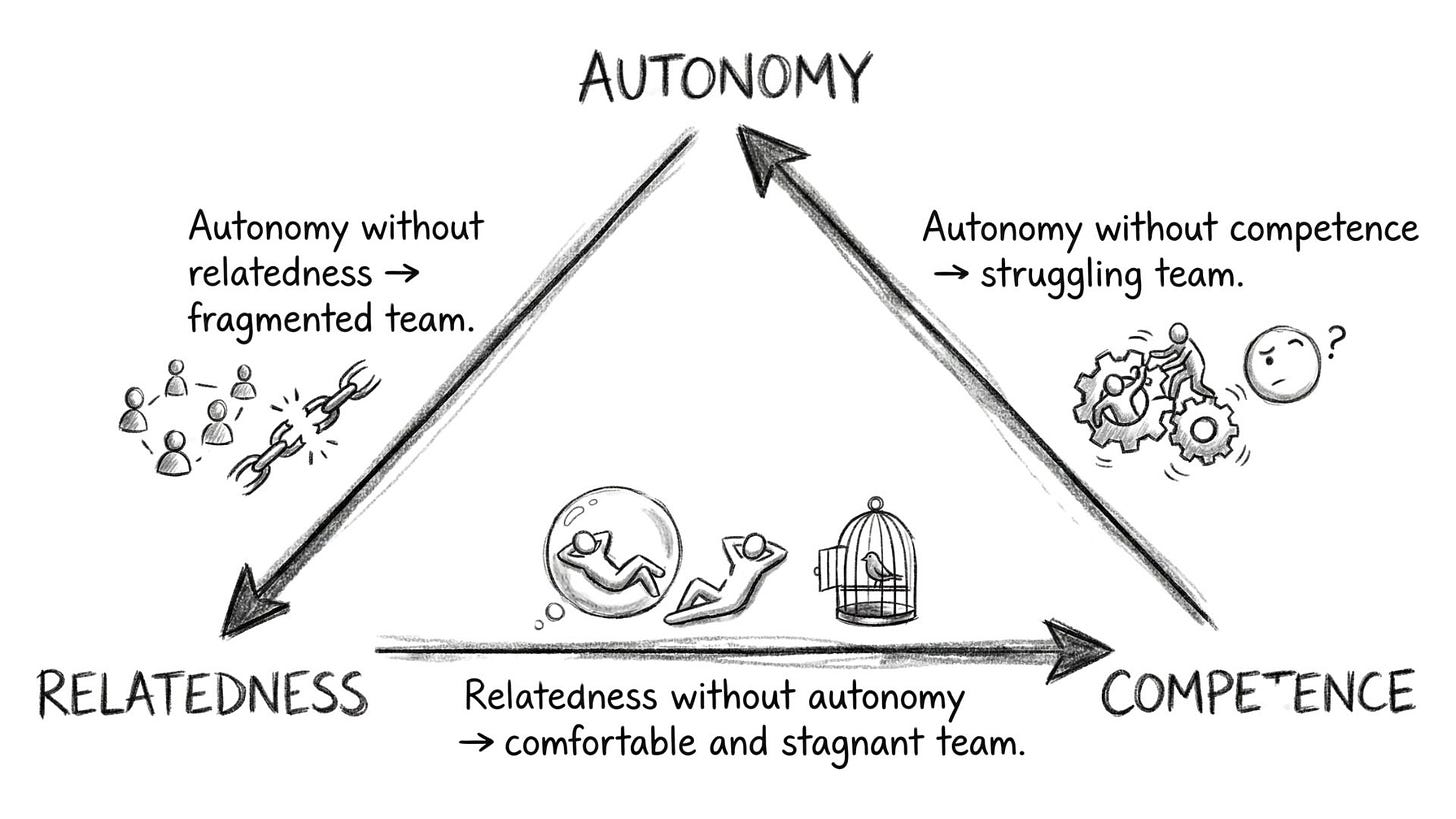

Psychologists Edward Deci and Richard Ryan spent decades developing Self-Determination Theory (SDT), one of the most validated motivational frameworks in psychology. According to their findings, humans have three core psychological needs that drive intrinsic motivation.

Autonomy: the feeling that you have genuine choice and agency over your work

Competence: the feeling that you’re effective, growing, and being challenged appropriately

Relatedness: the feeling that you belong and your contributions matter to people you care about

When any of these is suppressed, people move from intrinsic motivation ("I care about this") to extrinsic motivation ("I'm doing this because I have to"). The work might still get done. But creativity, persistence, and quality all decline.

A 2017 meta-analysis by Van den Broeck et al., covering 99,000+ workers, found that satisfaction of these three needs was significantly linked to commitment and performance, with “autonomy” as the strongest predictor.

Why does this matter to you?

It matters because your job (as a Scrum Master or Delivery Lead) is to create conditions where all three needs are met simultaneously.

Autonomy without relatedness → fragmented team.

Autonomy without competence → struggling team

Relatedness without autonomy → comfortable and stagnant team.

You need the full triangle.

But how?

First: Build Psychological Safety

I am pretty sure you already know this, but here’s a recap.

In the year 2012, Google ran one of the largest studies on team effectiveness ever conducted.

180+ teams. The variables measured were composition, seniority, intelligence, co-location, and workload.

What do you think was the most important factor for team effectiveness?

It was Psychological safety!

Psychological safety is the shared belief that the team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking.

This also aligns with Harvard professor Amy Edmondson’s research (she coined the term in 1999).

Her findings across hospitals, factories, and tech companies: Teams that openly discussed mistakes outperformed teams that hid them. Even when the "hiding" teams had more experienced members.

Here’s why this matters for Self-Determination Theory (SDT:

Psychological safety supports all three SDT needs at once.

→ Autonomy: “I can take risks.”

→ Competence: “I can admit what I don’t know.”

→ Relatedness: “These people have my back.”

So…

Before we can worry about autonomy, we should ask ourselves this one question:

“Does my team feel safe enough to disagree, flag risks, and admit mistakes?”

If the answer is no, fixing that is job #1.

Everything else builds on top of that.

Second: Improve Visibility

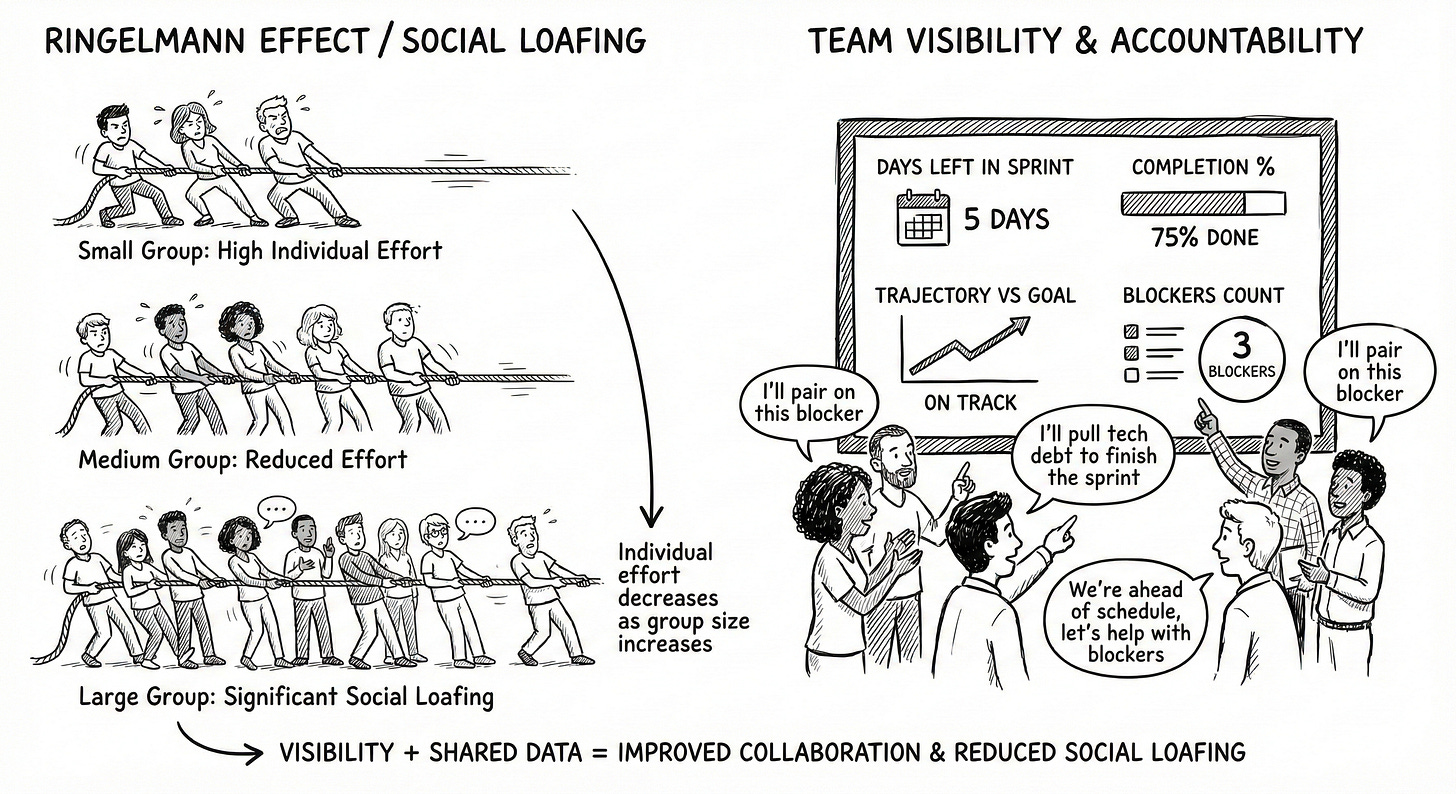

There’s a known phenomenon in psychology called the Ringelmann Effect. In the 1910s, a French researcher found that as group size increases, individual effort decreases.

The reason, it turned out, was that when individual contributions become less visible, the psychological incentive to give full effort weakens. Researchers call this Social Loafing.

What’s the fix?

Visibility!

Here’s what doesn’t work for visibility:

Jira issue updates. Time tracking. "What did you do today?" standups. Code commit metrics.

All of this is the wrong frame.

It's trying to measure inputs when what matters is outputs/outcomes. It's trying to solve an information problem with an enforcement problem.

Here’s what works for visibility:

Shared team state.

The best implementation I’ve seen is simple.

One big screen in the team space (or a pinned Slack channel for remote teams) that shows:

Days left in sprint

Committed work completion percentage

Current trajectory vs. goal

Blockers count

That’s it. Four numbers. Updated automatically every hour. It shows where the team is relative to where the team said they'd be.

Here's what happens when you implement this:

The team self-corrects.

When sprint goal is behind? Someone says, “I can defer my discretionary work and pair on the sprint goal work.”

When the sprint goal ahead of track? Someone says, “I’m going to pull that tech debt item we’ve been wanting to fix.”

The accountability becomes collective.

And it’s immediate.

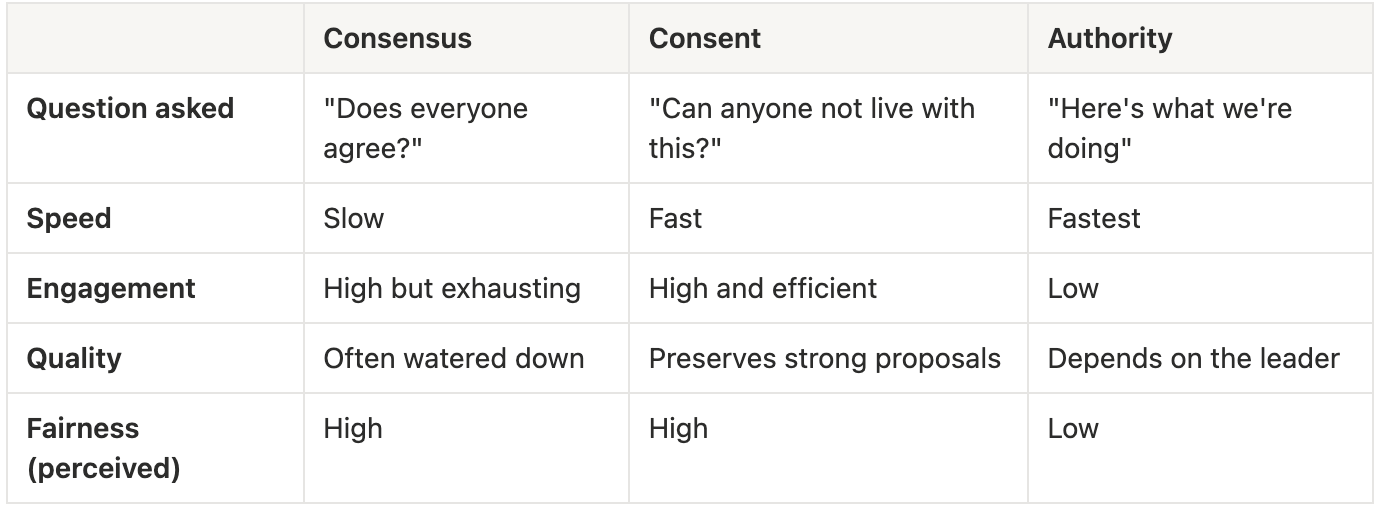

Third: Replace consensus with consent

This is a small change, but it saves a huge amount of time.

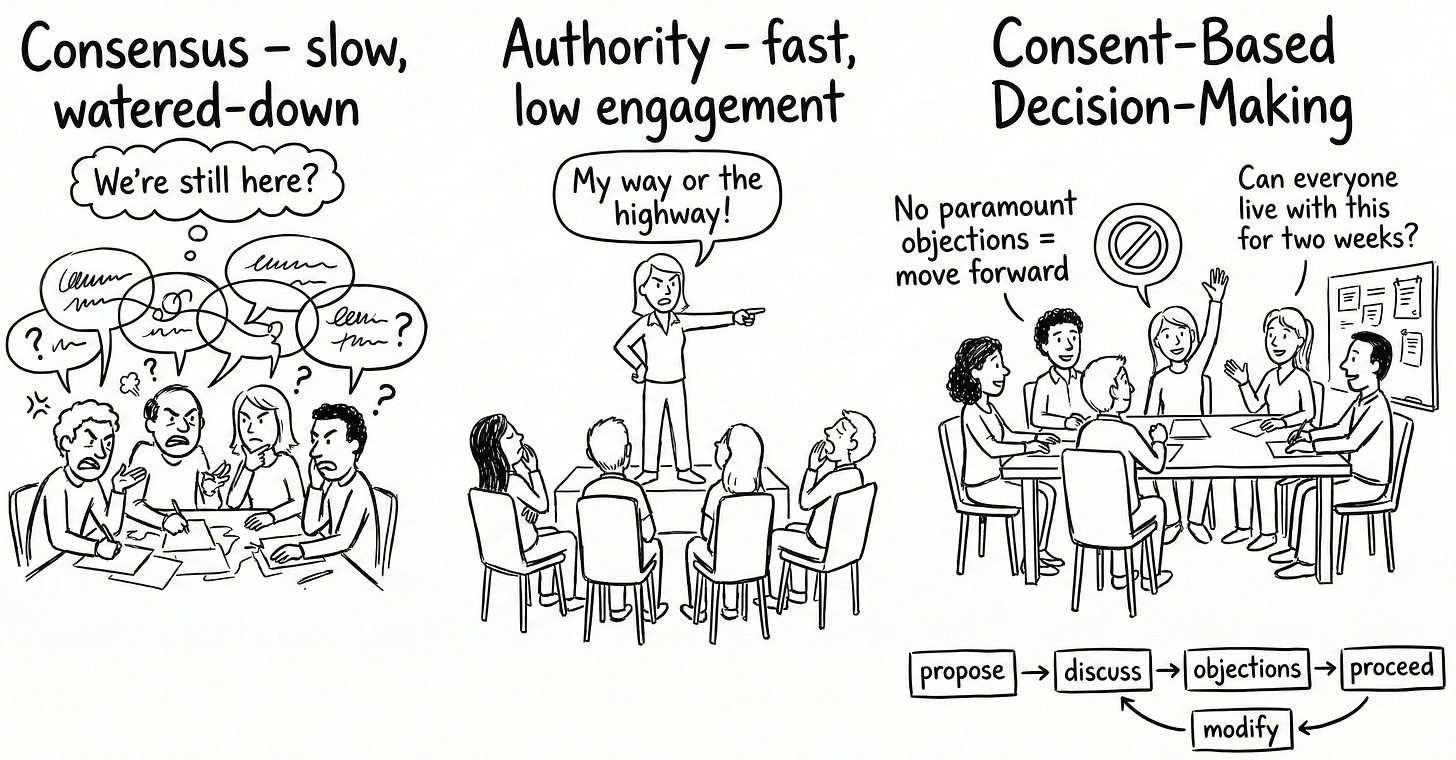

Most teams default to one of two decision-making modes:

consensus (everyone must agree)

authority (the lead decides)

Both have problems.

Consensus is slow and produces watered-down compromises. Authority is fast but kills engagement.

There's a better model, drawn from sociocratic governance:

Consent-based decision-making.

It’s the middle ground.

Consent requires the absence of a reasoned, paramount objection.

Anyone can raise an objection, and objections are taken seriously. But "I would have done it differently" isn't an objection.

Research on procedural justice consistently shows that people accept outcomes they would prefer not to have when they believe the process was fair. Being heard matters more than winning.

Here’s how to do it:

After every discussion where you need to make a decision, ask: "Can everyone live with this for the next two weeks, even if it's not your first choice?" If someone can't, they explain why, and the proposal is modified accordingly. If everyone can, you move.

How much freedom does your team actually need?

If you’ve read this far, you might be thinking the message is simple: give people more autonomy, more ownership, more space and good things follow.

That's half right. And the other half is where many delivery leads get into trouble.

Autonomy is a judgment call. The amount of freedom your team needs depends on what’s actually happening right now. Some sprints need a lighter touch. Some need a firmer hand. The skill isn’t in picking one approach. You must know when to move between them.

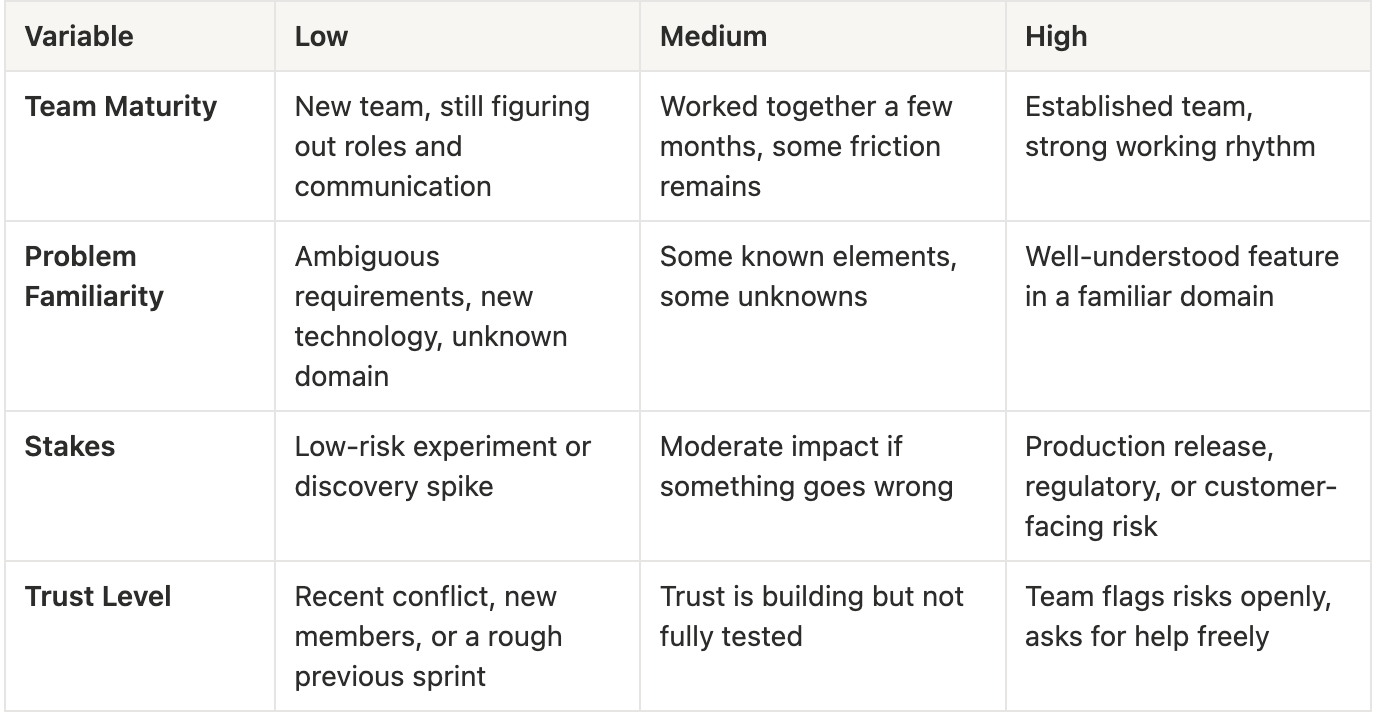

There are four variables to help you decide when and how much to move.

1. Team Maturity

A team that formed two months ago is still figuring out:

how to communicate,

who does what, and

how to handle disagreements

They need clearer roles, shorter feedback loops, and more frequent check-ins.

A team that's been shipping together for two years already has those things figured out.

They need space to do their thing.

Treat them accordingly.

Tuckman’s model (forming → storming → norming → performing) is a cliché because it’s true.

Don’t give a forming team the autonomy of a performing team.

2. Problem familiarity

If they've built something similar before in a domain they know well, step back and let them do their stuff.

But if the requirements are unclear, the technology is unfamiliar, or no one is really sure what "done" looks like, then shrink the feedback loop.

Check in more.

Small misunderstandings in unfamiliar territory compound quickly, and catching them early is the whole point of tighter feedback loops.

3. Stakes

Not all work carries the same risk.

Low-risk experiment? Let them explore freely

High-risk production release? Stay closer, coordinate tighter

That's just responsible behavior, not controlling.

4. Trust level

Trust is the variable that amplifies or undermines everything else.

When trust is high, people flag risks early, ask for help without hesitation, and hold each other accountable without being asked. Here you can lean heavily into autonomy.

When trust is low, maybe someone new just joined, maybe the last sprint went sideways, maybe there's an unresolved tension, add more visibility and more structure.

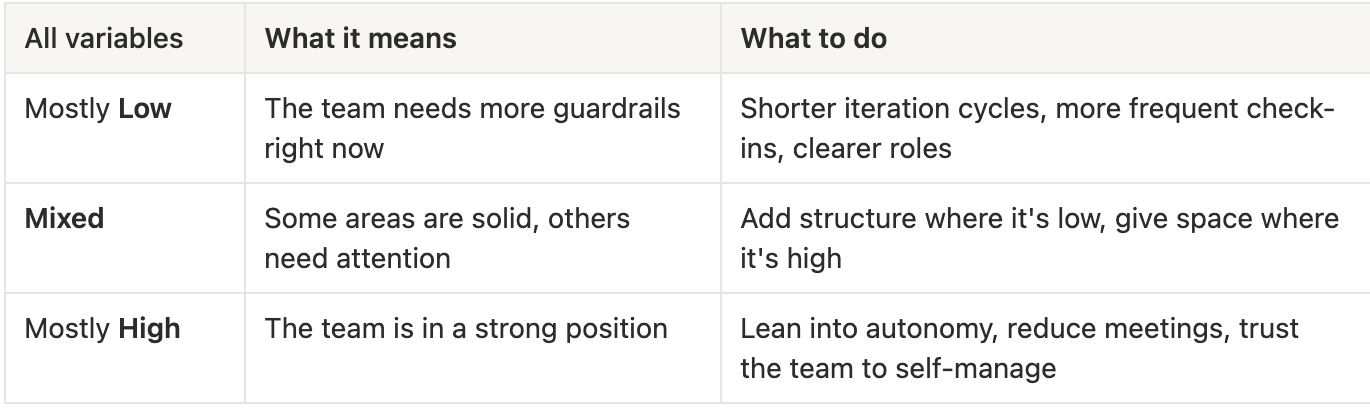

Here’s how to implement these 4 variables:

Rate each of these four variables in your team as low, medium, or high.

Read the results:

Fill this out at the start of every sprint. Keep a running log.

After a few months, you'll spot patterns like which variables tend to dip before a rough sprint, and you'll start making adjustments before problems surface instead of after.

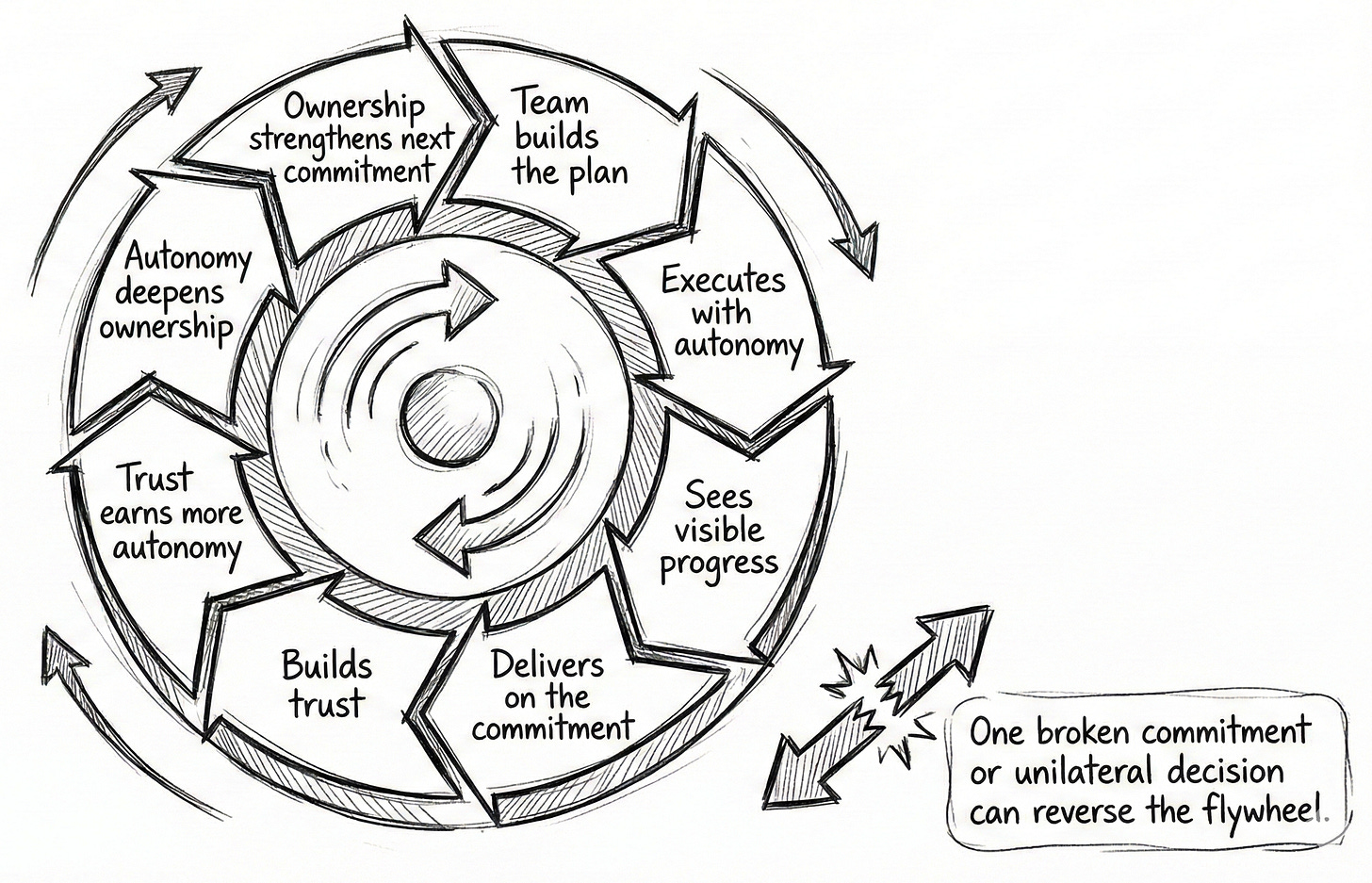

The Progress Principle

Everything above works as a system and not as a collection of disconnected activities.

Here’s why.

Teresa Amabile and Steven Kramer collected nearly 12,000 daily diary entries from 238 professionals across 26 project teams.

According to their findings, which were published as The Progress Principle:

The single most important factor in sustaining motivation and engagement was making progress on meaningful work.

Not big wins.

Small. Daily. Visible. Progress.

This is what creates the flywheel:

Team builds the plan → executes with autonomy → sees visible progress → delivers on the commitment → that builds trust → trust earns more autonomy → autonomy deepens ownership → ownership strengthens the next commitment → the flywheel keeps rolling.

But… be cautious, as it can spin both ways.

One commitment broken without acknowledgment. One decision made unilaterally that should’ve been made by the team. One person who flags a risk and is blamed.

These things can reverse the flywheel.

Takeaway…

Don’t try to balance autonomy and commitment.

Build a structure that produces autonomy and commitments that people choose to keep.

That’s it.

That’s the whole game in Ocean’s Eleven.

Show your support

Every post on Winning Strategy takes a few days of research and 1 full day of writing. You can show your support with small gestures.

Liked this post? Make sure to 💙 click the like button.

Feedback or addition? Make sure to 💬 comment.

Know someone who would find this helpful? Make sure to recommend it.

I strongly advise that you download and use the Substack app. This will allow you to access our community chat, where you can get your questions answered and your doubts cleared promptly.

Further Reading

Connect With Me

Winning Strategy provides insights from my experiences at Twitter, Amazon, and my current role as an Executive Product Coach at one of North America’s largest banks.