How do teams improve their delivery efficiency?

Metrics that help teams improve delivery and predictability.

Let’s say you are a Product Owner.

And your team is planning a Sprint… again!

“How much can we commit to this sprint?” someone asks you to predict.

You look at your team’s velocity from the last three sprints. You average it out. You throw in a fudge factor because, well, you always do. And then you make your best guess.

The thing is, you’re actually not predicting anything.

You’re just… hoping.

I’ve watched Product Owners struggle with this for years.

“Why did this take three weeks?” or

“How do we get faster?” or

“Where is work actually getting blocked?”

These questions can sometimes be quite difficult to answer.

So…

How do experienced teams answer these questions?

Let’s find out.

If you are new to Winning Strategy, check out the posts below that you might have missed

Got an urgent question?

Get a quick answer by joining the subscriber chat below.

Delivery Metrics for Product Owners

As a Product Owner, your job isn’t just to prioritize what to build.

You’re also on the hook for “when” stakeholders can reasonably expect to see outcomes.

Delivery metrics help you do that.

They give you a clear view of how smoothly work moves through the team from idea to Done, and how consistently the team meets its commitments.

Let’s look at each of these metrics one by one.

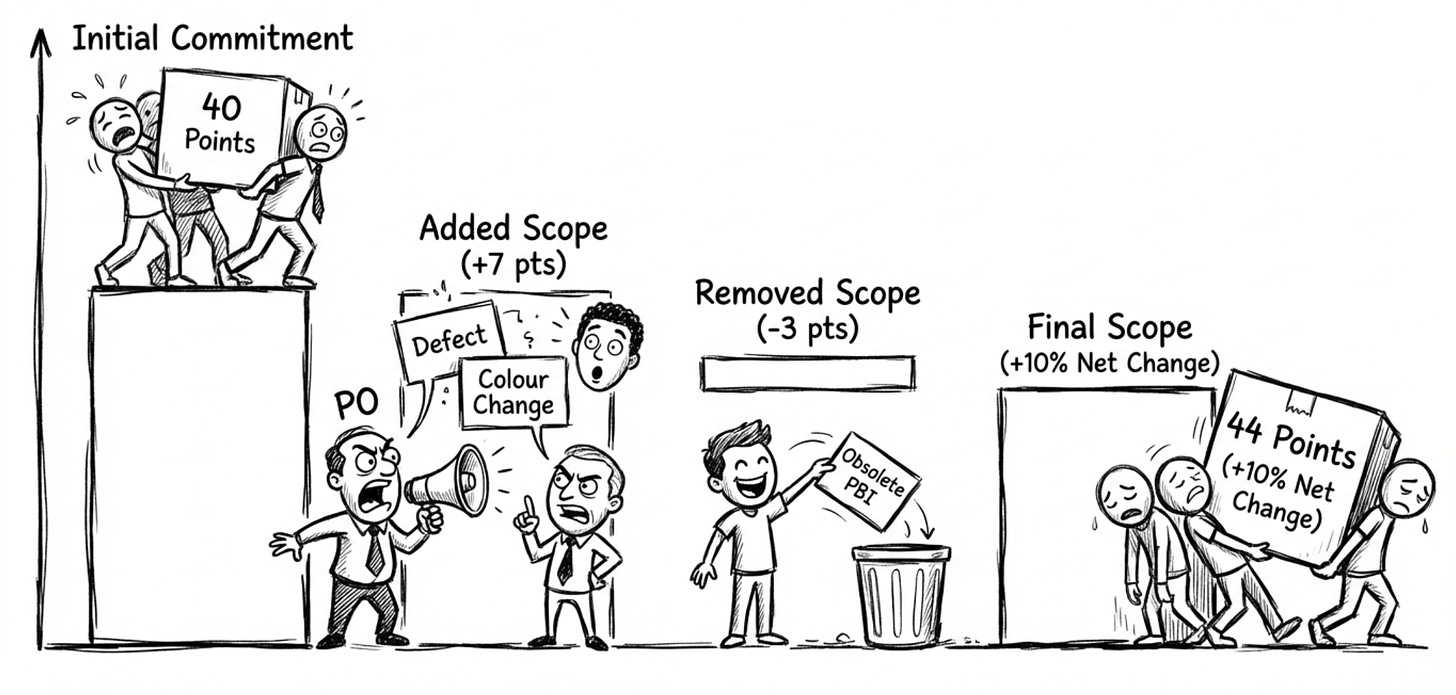

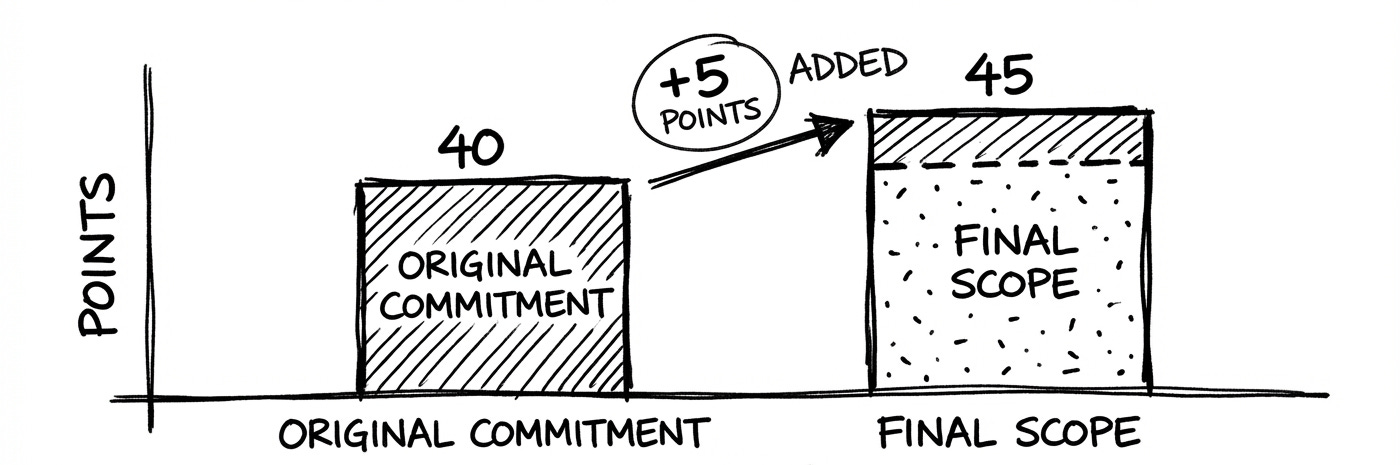

#1 Scope Change Inside the Sprint

This is the amount of work added, removed, or changed in scope while a sprint is “in progress.”

A Sprint Backlog that keeps changing makes any velocity based forecast meaningless.

It indicates misalignment between PO, stakeholders, and the team.

To use this metric:

Capture the numbers. Create a simple chart for each Sprint: original commitment vs. final scope

Bring the data to the Retrospective.

Highlight which changes were “true emergencies” versus “nice-to-have”

Discuss what upstream decisions, alignment, or communication can reduce the scope change in future

Example:

Let’s say your Sprint begins with 40 story points across 10 PBIs.

Day 4: Customer support escalates a production defect (5 pts) → added.

Day 6: Marketing drops a low-value UI colour change request (2 pts) → added.

Day 8: Team realizes a planned PBI is obsolete (3 pts) → removed.

Scope change: +7 pts, –3 pts ⇒ net +4 pts (10% increase).

In the Retro, the team decides the following:

The production defect was valid

The colour change could have waited; the PO will (from now on) redirect such requests to the next Sprint unless revenue is at risk

The obsolete item signals we need better grooming with the stakeholder two weeks earlier

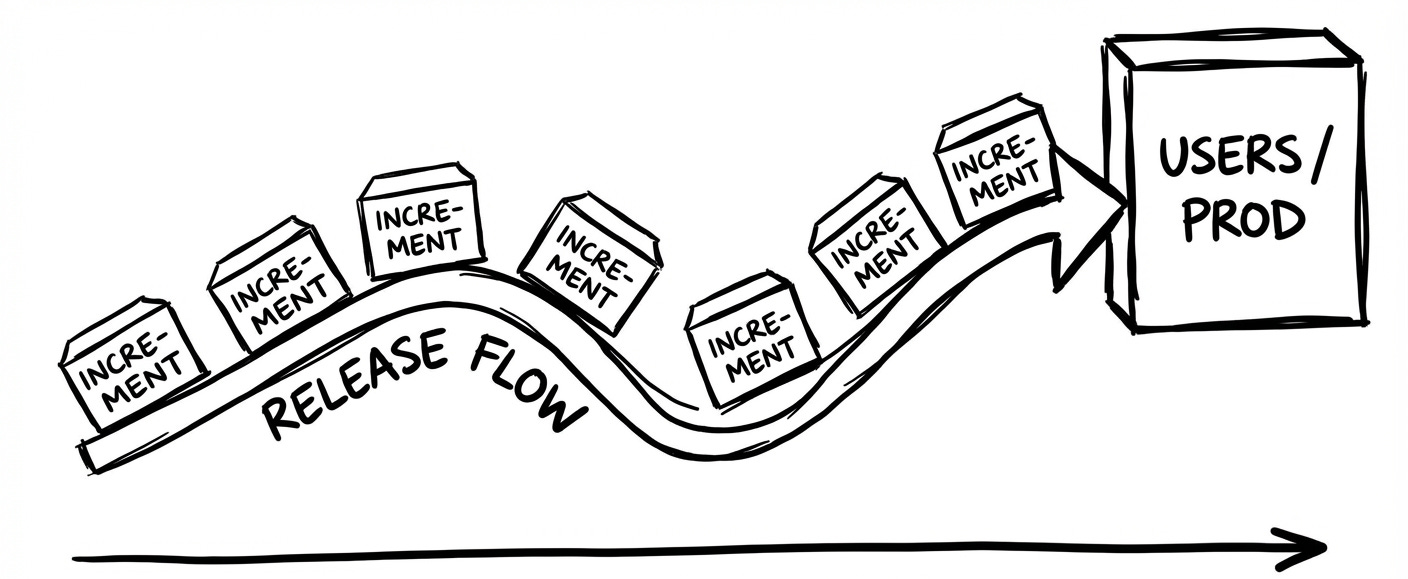

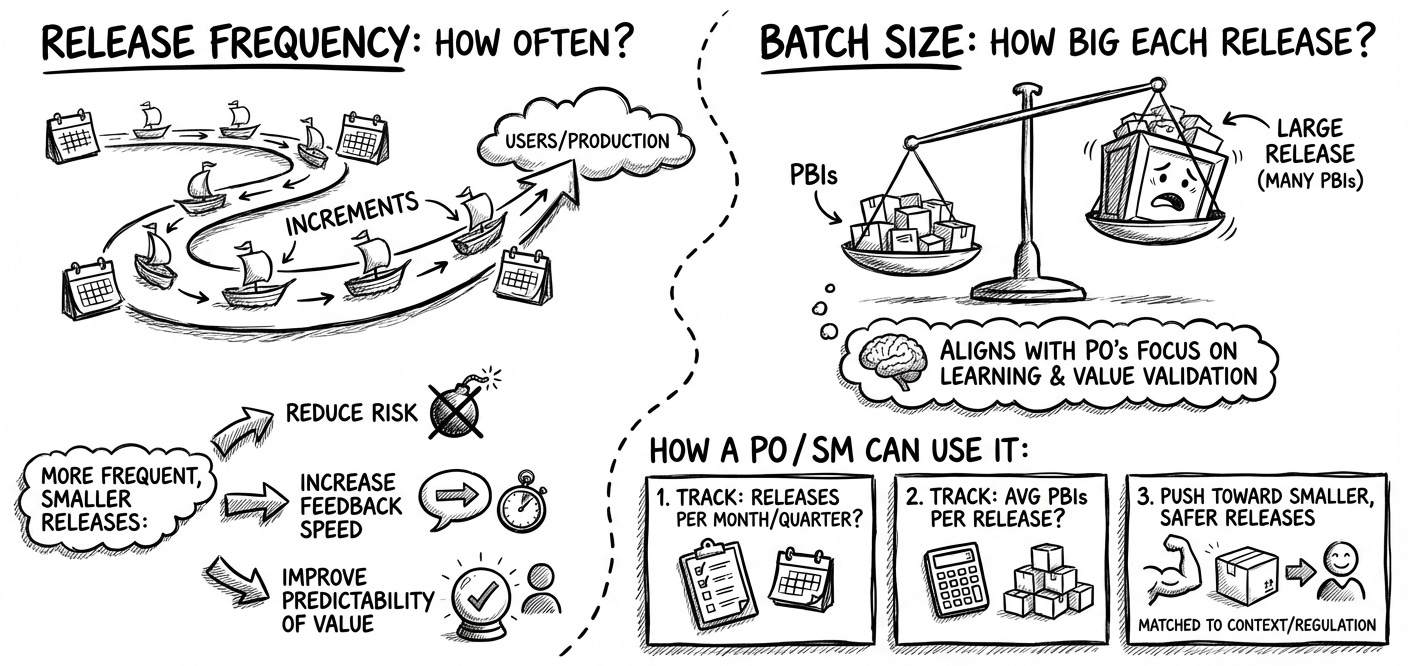

#2: Release Frequency and Batch Size

Release Frequency:

How often does the team push increments to users/production?

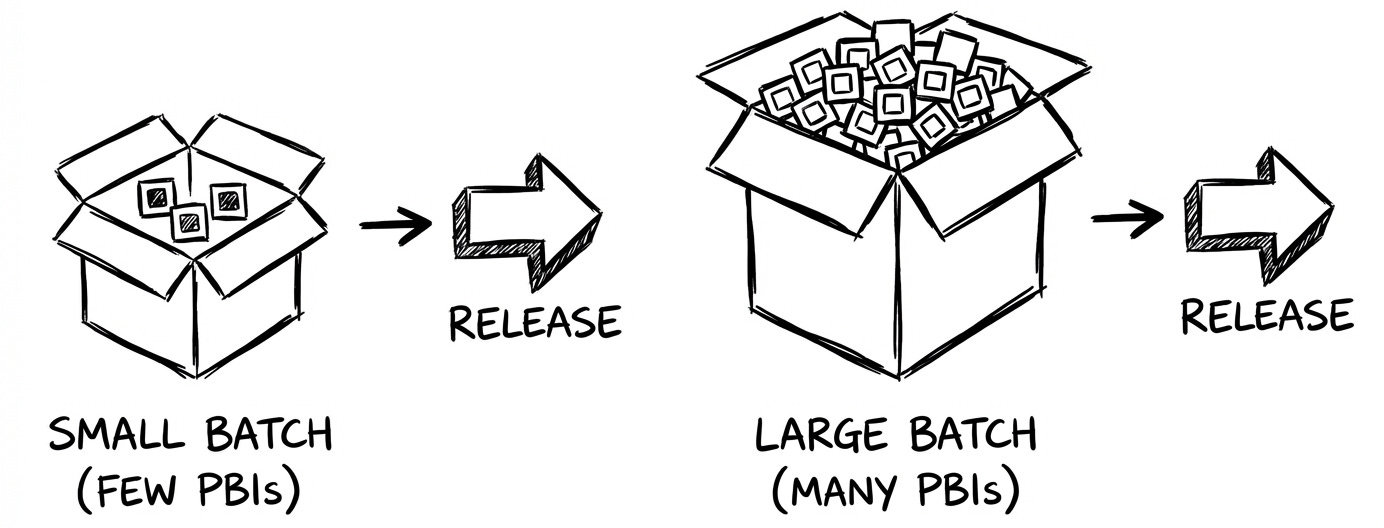

Batch Size:

How big each release is (number of PBIs per release)?

More frequent, smaller releases:

Reduce risk

Increase feedback speed

Improve the predictability of value reaching users

And it aligns with the PO’s focus on learning and value validation.

How a PO / SM can use it:

Track: how many releases per month/quarter?

Track: average number of PBIs per release

Push toward smaller, more frequent, safer releases, matched to your context/regulation

Example:

Let’s say the current state is:

Releases: 1 every two Sprints

Batch size: ~ 20 PBIs

Post release defect rate: 5 critical bugs/release

Actions the team takes:

PO & Dev Team slice PBIs so each delivers user visible value

DevOps introduces automated tests and blue-green deploys

Team adds working agreement: “Release whenever main branch is green. Aim for daily.”

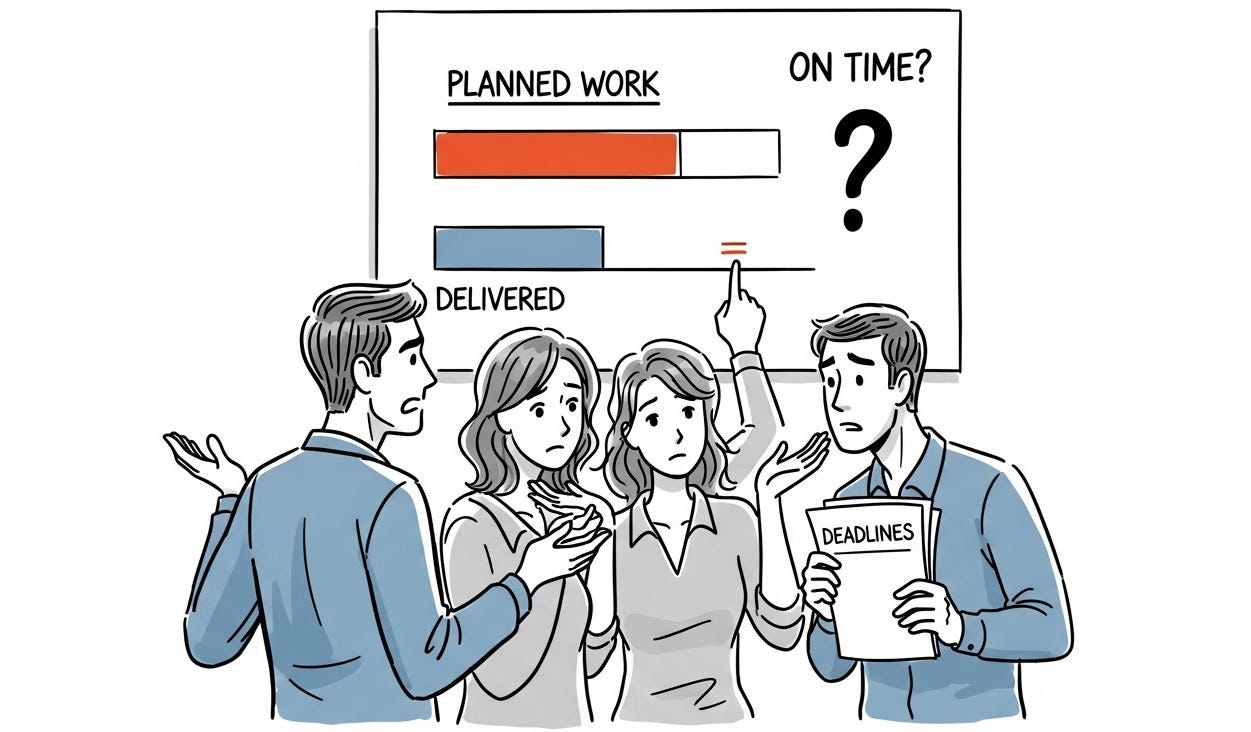

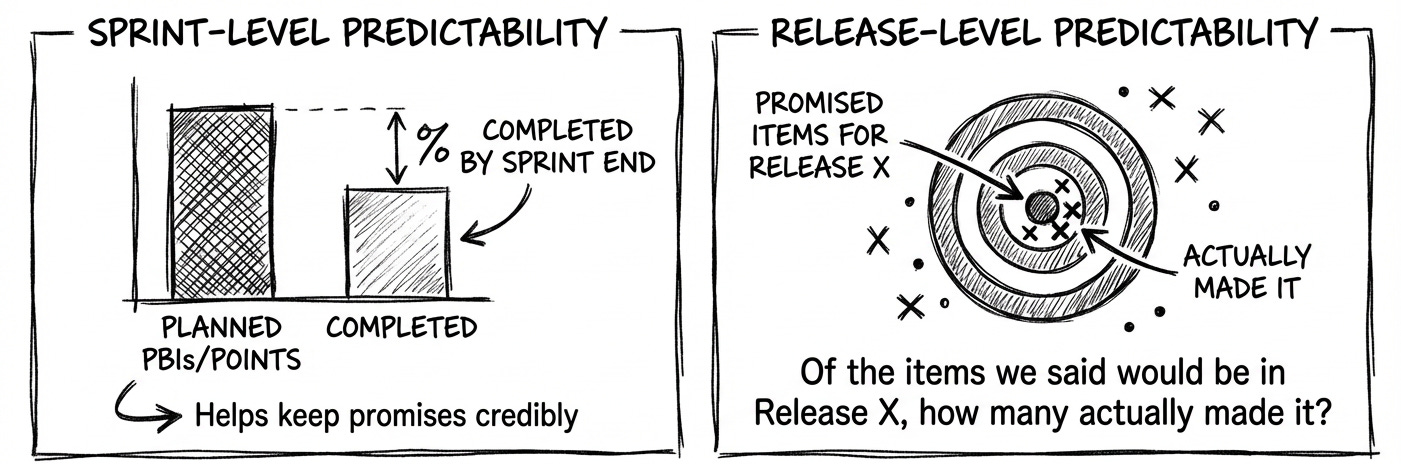

#3: Forecast Accuracy

This metric measures how often the team delivers what they forecast when they said they would.

There are two perspectives of this metric:

Sprint-level predictability:

% of planned PBIs completed by the end of the sprint (or planned vs. delivered points)Release-level predictability:

“Of the items we said would be in Release X, how many actually made it?”

This metric helps POs credibly keep their promises.

Here’s how:

Every Sprint SM and PO track the following:

Planned vs. Delivered (stories or points)

Whether the Sprint Goal (not just items) was delivered

Then… they use historical data to right-size commitments and avoid overcommitting.

Example:

Let’s say in the last Sprint:

Commitment: 10 PBIs (40 pts).

End of Sprint: 7 PBIs done (30 pts).

Accuracy: 70%

Using that data, the Product Owner redraws the commitment to the 7 (highest-value) PBIs and tells stakeholders:

“Based on history, this gives us an 80% confidence of completion.”

This metric reduces the guesswork.

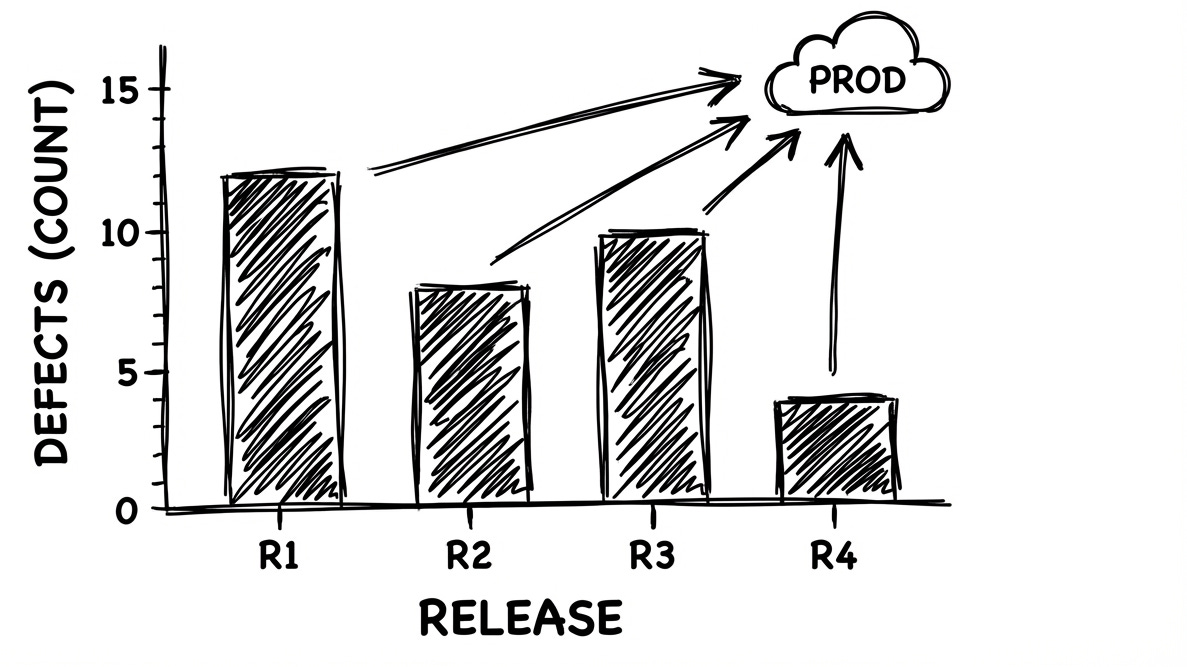

#4: Defect Escape Rate

Number of defects found in production per release.

Defect Escape Rate provides input for prioritization.

For example, a consistently high escape rate is a strong signal that your team should invest in quality improvements and reducing technical debt.

Example:

Let’s say in the current release cycle:

Releases: 4 over the past 3 months

Escaped defects: 9 total (4 critical, 5 minor)

Escape rate: 2.25 defects/release

How the metric can help:

PO can use the 4 “critical” escapes to justify dedicating 20% of the next Sprint to regression test automation and refactoring.

The Scrum team can use it as a signal to add “automated test in CI” to the DoD.

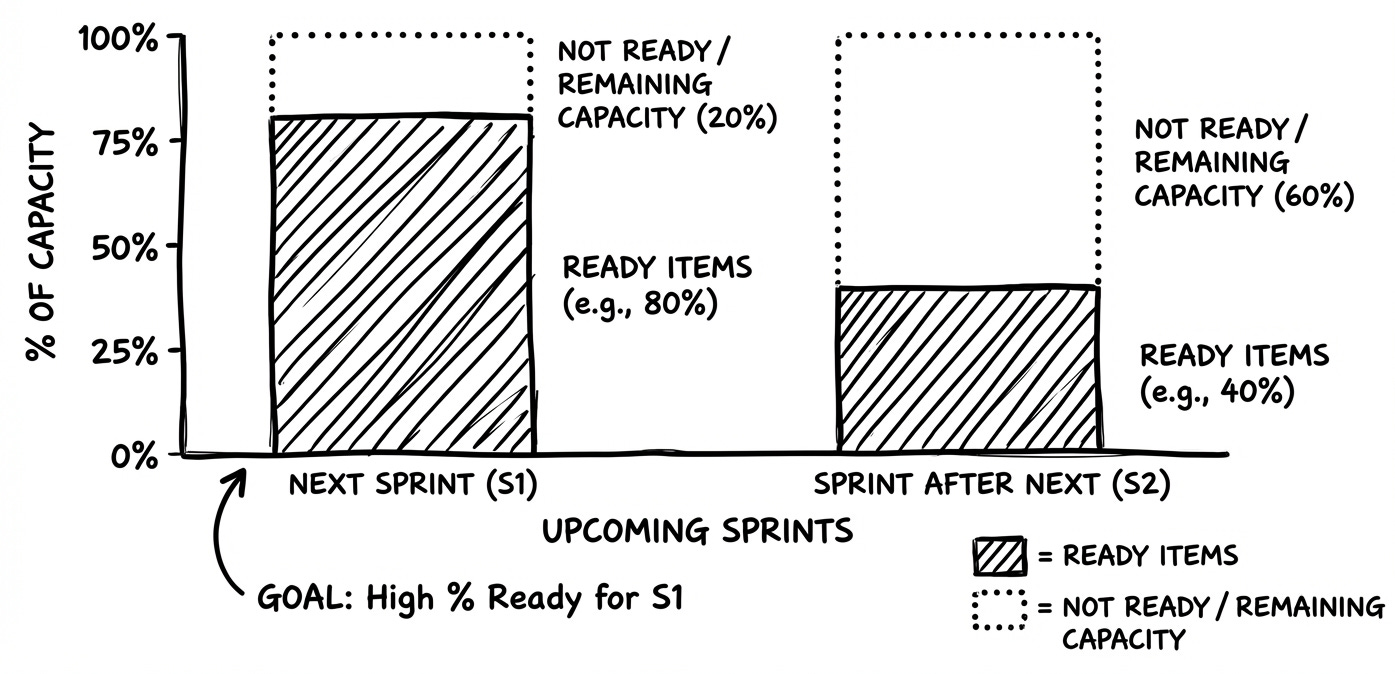

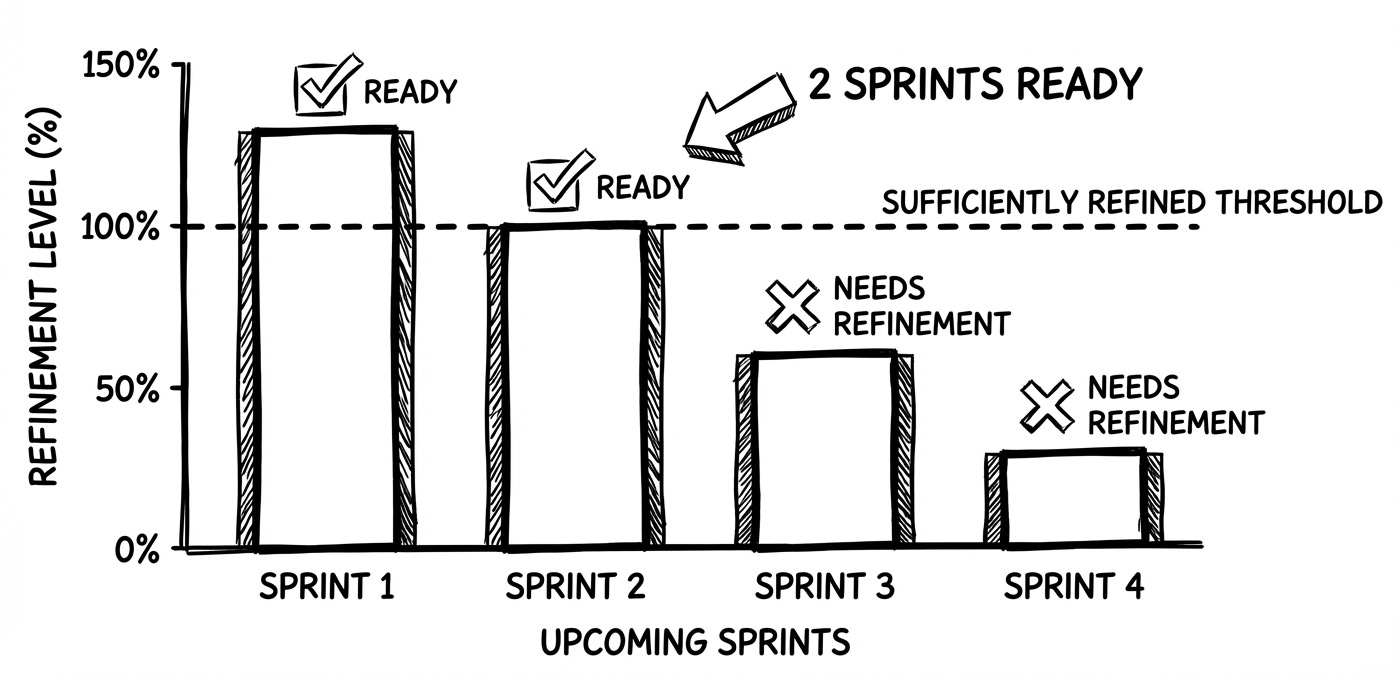

#5: Backlog Readiness

The proportion of upcoming work that is refined enough to be pulled into a sprint without further adjustments.

There are two perspectives of this metric:

% of items (out of team’s capacity) for the next 1–2 sprints that meet a clear “Ready” checklist

Number of upcoming sprints with sufficiently refined work

Backlog readiness directly affects planning stability. Items that are NOT READY lead to mid sprint surprises and rework.

Example:

Let’s say before Sprint Planning:

Ready PBIs: 18 items = 80 pts

Team’s typical Sprint capacity: 40 pts

Readiness: 200% (≈ 2 full Sprints of pull ready work)

PO notices the backlog is “over groomed.”

So she pauses further detailing beyond the next Sprint, and instead schedules testing sessions to validate the backlog’s assumptions.

Team reallocates refinement time to handle techdebt tasks.

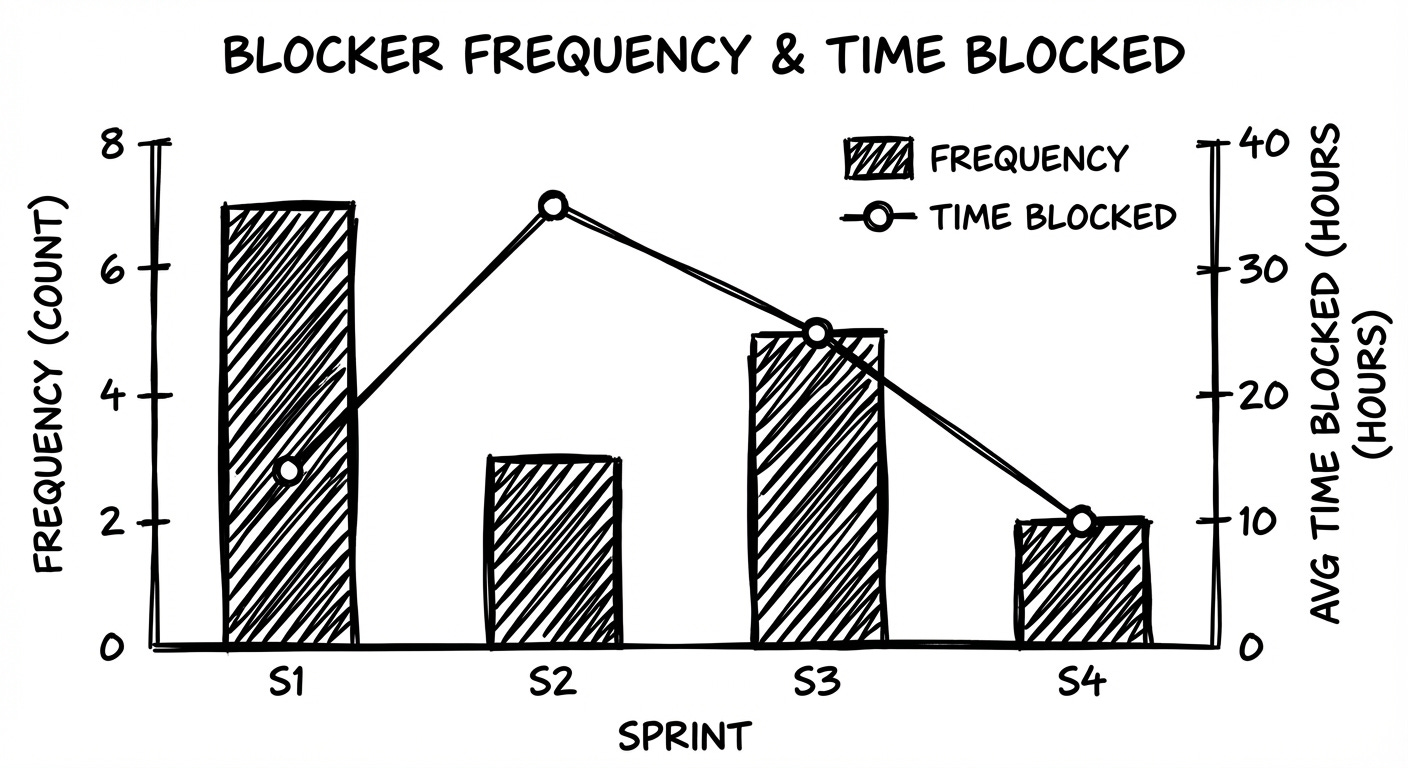

#6: Blocker Frequency and Time Blocked

Blockers are simply work items that get stuck.

Blocker frequency is how many items get blocked in a sprint

Time blocked is how long, on average, they stay stuck

Most blockers are not technical. They’re about decisions.

Things like:

missing clarification or acceptance criteria

stakeholders deciding too late, or

dependencies on other teams

Those are the kinds of issues a Product Owner can often influence or remove.

Example:

Let’s say in the current Sprint:

Commitment: 10 PBIs

Blocker frequency: 4 PBIs entered “Blocked”

Average time blocked: 2.5 days

Further investigation showed that items are pending due to delayed stakeholder approval.

PO can use this data to convince stakeholders and make decisions like setting up a standing 15-minute daily slot with that stakeholder.

#7: Work in Progress

Number of PBIs in progress at any given time.

High WIP = context switching, slower delivery

As PO, you influence how much is started vs. how much is finished. Lower WIP improves flow and predictability.

Example:

Let’s say halfway through the Sprint:

Team capacity: 4 developers

WIP shown on the board: 9 PBIs across In Progress (WIP limit was set to 6 → they are +3 over)

Each dev is juggling 2+ items, so there is a lot of context switching.

What to do?

Seeing WIP = 9, the PO pauses new starts and inquires why the WIP is high.

It is high because “peer review,” which is part of the “in progress” stage, is taking longer than anticipated.

This makes PO take actions such as helping clear review queues by pairing reviewers, and clarifying acceptance criteria.

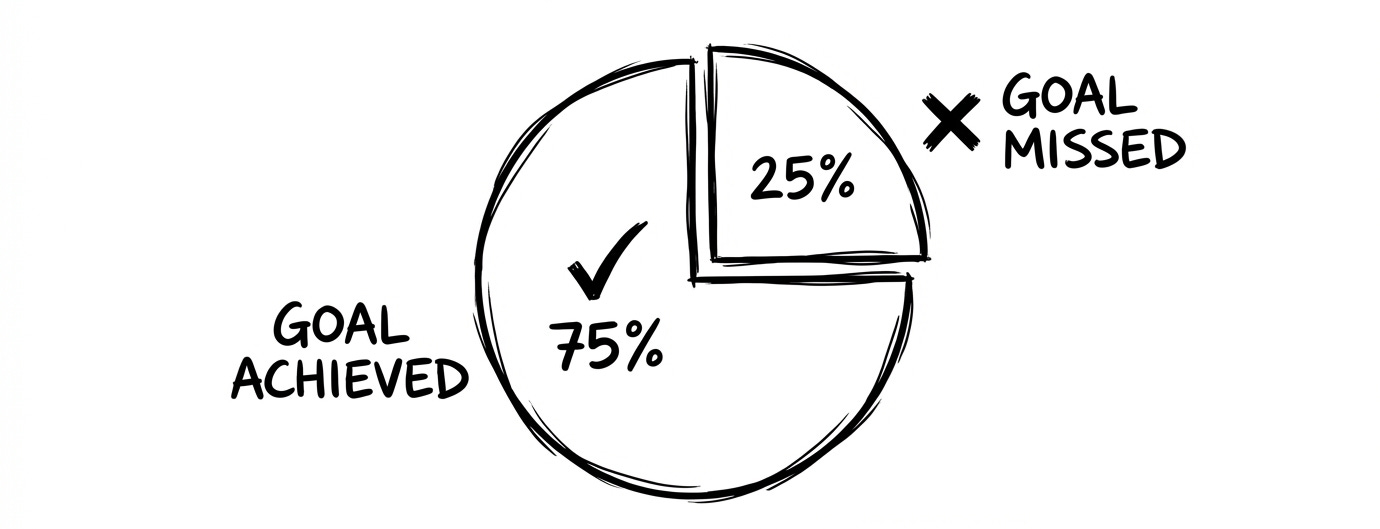

#8: Sprint Goal Success Rate

The ratio of Sprints whose Sprint Goal was fully achieved to the total number of Sprints observed.

Success Rate = Sprints with Goal Met ÷ Total Sprints × 100 %This is a direct measure of predictability.

This tells how well your team is slicing and planning, and whether it is protected from scope creep.

Example:

Let’s say over the last 6 Sprints:

Goals fully met: 3

Goals partially met: 2

Goals missed: 1

Sprint Goal Success Rate: 50 %

Only half of the Sprints produced the exact outcome the PO promised.

Review of the two “partial” Goals showed both were derailed by scope additions made mid Sprint.

Knowing this, the PO can introduce a working agreement: “No new work enters the Sprint unless the PO and Dev Team agree it’s critical.”

Takeaway

Delivery flow and predictability metrics give you, as a Product Owner, the evidence you need to make better calls:

What can we realistically promise, and by when?

Where is work getting stuck, and what can I do to unblock it?

Are we trading off too much quality for speed?

How confident can we be in our next release?

Used well, these metrics can change the conversation with your stakeholders.

You are no longer required to defend missed dates. You can show how the system is performing, what you’re doing to improve it, and what level of certainty they can expect.

Show your support

Every post on Winning Strategy takes ~ 3 days of research and 1 full day of writing. You can show your support with small gestures.

Liked this post? Make sure to 💙 click the like button.

Feedback or addition? Make sure to 💬 comment.

Know someone who would find this helpful? Make sure to recommend it.

I strongly recommend that you download and use the Substack app. This will allow you to access our community chat, where you can get your questions answered and your doubts cleared promptly.

Further Reading

Connect With Me

Winning Strategy provides insights from my experiences at Twitter, Amazon, and my current role as an Executive Product Coach at one of North America’s largest banks.