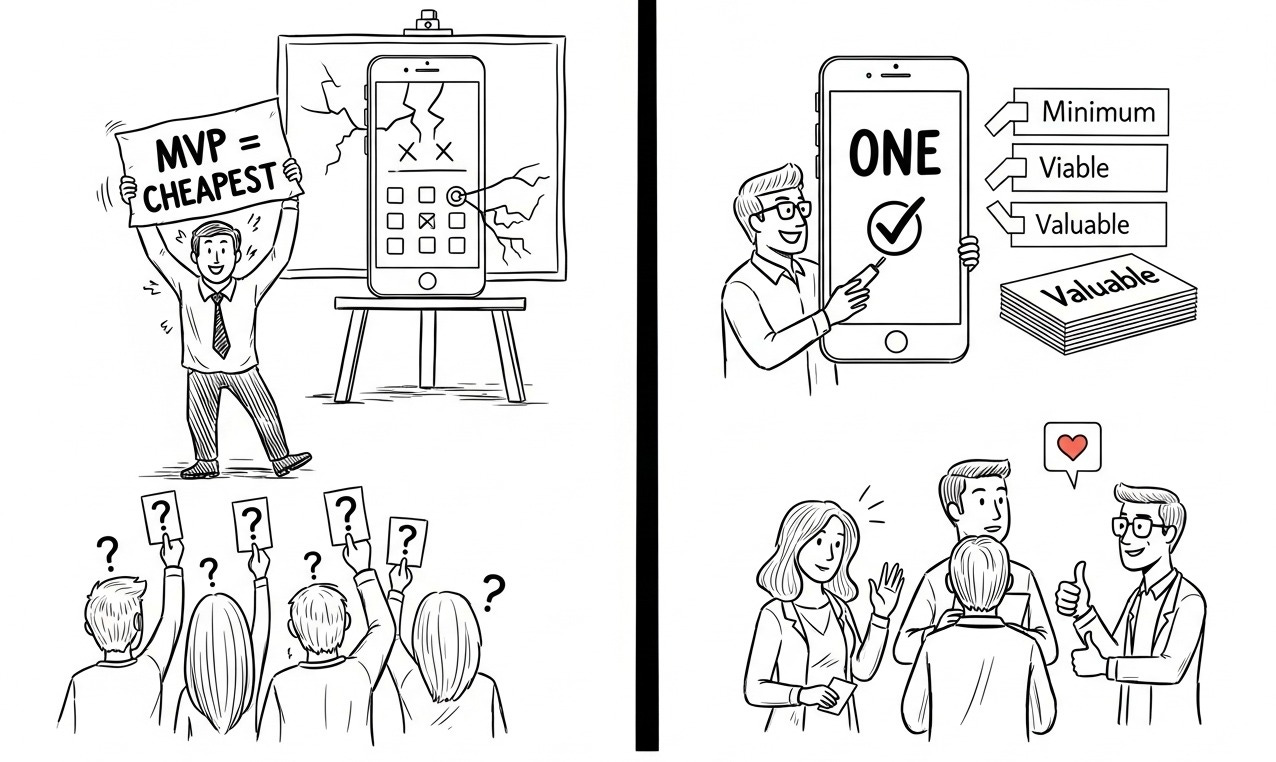

MVP is the cheapest possible prototype.

Why is this a BIG misconception and how mature teams keep their MVPs minimum, viable and valuable?

“How cheap can we make it?”

If you’ve heard this question when discussing MVPs, you know exactly what I am talking about.

For years, I’ve watched teams, as well as experienced leaders, confuse “MVP” with “the absolute bare minimum.” It’s one of those mistakes that everyone makes at least once in their product journey.

When Executives hear “Minimum Viable Product,” they picture a few lines of code with minimum cost.

That’s not what an MVP is.

An MVP isn’t about “spending” at all.

It is about “learning.”

In today’s post, I will share a few simple and straightforward strategies that mature teams use to ensure they get the most learning from their MVPs.

Let’s get started.

If you are new to Winning Strategy, check out the posts below:

Got an urgent question?

Get a quick answer by joining the subscriber chat below.

Why the misconception is sooo… attractive

“MVP = the cheapest possible prototype.”

At first glance, “cheapest prototype” feels like a sensible definition for an MVP:

it keeps spending low,

fits Agile’s misconception of speed, and

sounds safely disposable

Sounds like a business dream… right?

Well, before we wake up those who are dreaming this dream, let’s first understand why their dream feels so real and tempting in the first place.

Reason #1: Budgets are tight, and “cheap” sounds responsible

When money is scarce, any initiative sold as “cheaper” earns instant goodwill from executives and finance teams.

The label feels fiscally prudent, so it sails through approvals with less scrutiny than bigger ticket requests.

Reason #2: Agile = Speed

There are many misconceptions about Agile. One of the most common misconceptions is:

Agile = Speed.

Because teams showcase short sprints and rising burndown charts, “moving fast” becomes the most important metric.

It’s easy, then, to equate success with delivering anything quickly.

So people trim away functionality and user value, just to close tickets faster.

The result is “speed” without validated learning.

Reason #3: “Prototype” is familiar to engineers

Prototypes promise that we can throw them away later.

Engineers are comfortable with Prototypes. They signal freedom to code quickly, skip robustness, and “figure it out later.”

That familiarity lowers psychological resistance. For example:

Stakeholders hear “prototype” and assume disposability

Developers become less quality disciplined

These three are the most common reasons why no one truly understands (or even wants to understand) what an MVP really is.

What an MVP really is

The reasons above make the MVP/Prototype misconception look attractive.

That framing, though, ignores the primary goal of an MVP:

Minimum – the smallest complete slice of the product that can validate (or invalidate) a risky assumption

Viable – valuable enough that real users will use it in a real setting AND give trustworthy feedback

Product – intended for production use, not an internal demo. It must meet a lightweight Definition of Done (security, usability, compliance, etc.)

Eric Ries: “An MVP is designed to maximize validated learning per unit of effort.”

Cheapest ≠ Maximum validated learning.

Prototype ≠ Viable.

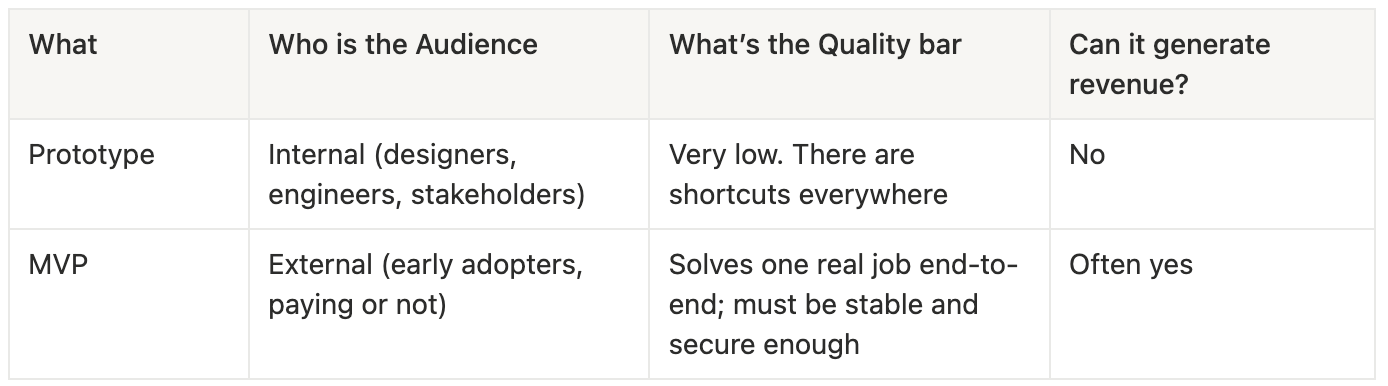

Prototype vs. MVP

A Prototype often exists before any backlog item.

An MVP is a backlog item (or a series of them) that will be incrementally improved and is never discarded.

To learn more about how to choose an MVP, check out the post below for an in-depth explanation:

In short:

An MVP is the smallest slice of the product. This slice:

Solves ONE meaningful user problem end-to-end

Enables you to observe genuine user behaviour (not just interview answers)

Is built at a quality level that doesn’t corrupt the signal or feedback (no crashes, no data loss, basic security)

If any of those are missing, you’re not validating viability. You’re just collecting noise cheaply.

What happens when teams believe in the misconception

Let’s say your team wants to add payments to a SaaS product.

The “cheap MVP” thinking would sound like:

“Let’s add a simple payment form that emails our finance team. They’ll manually process cards and send confirmation emails. Easy!”

But, if users require instant payment confirmation to access the facility or reserve a time slot, for example, this “cheap” version IS NOT viable at all.

Why?

Because with manual processing, they submit payment... and wait.

Maybe 4 hours. Maybe until the next business day. Meanwhile, they can’t complete their booking, confirm their reservation, or use the product for its intended purpose.

So, they will abandon the MVP and revert to their old solution, i.e., calling the facility directly and paying with a card over the phone, which provides instant confirmation.

Such an MVP will not validate (or provide any feedback) on whether people want the feature because it doesn’t actually solve their problem well enough for them to use it.

However…

It will validate insufficient adoption.

With this validation, you will conclude, “Users don’t want to pay through our platform.”

Which, in fact, is the wrong lesson.

You didn’t test whether users want the feature at all. You tested whether users will tolerate a broken workflow.

They won’t tolerate it!

What does the viable version look like?

The minimum viable version needs automated payment processing with instant confirmation, even if you use a 3rd party service like Stripe, which might incur additional costs for integration.

Yes!

It takes more effort up front.

But now users can actually complete their workflow.

Only then can you learn: “Do users prefer paying through our platform versus their current method?”

MVP has nothing to do with how much you “spend.”

It is about crossing the threshold where users can actually adopt the feature in their real world context.

How do mature teams ensure they have the correct version of the MVP, not just a cheap Prototype?

The fundamental difficulty here is that you CAN’T know if something is truly viable UNTIL users interact with it in real world conditions.

But…

By the time you’ve built it and discovered it’s not viable, you’ve already spent the time and money.

It’s a classic chicken-and-egg problem.

Mature teams solve this by being deliberate about:

Clarity on what they’re testing

Honesty about the viability threshold

Discipline in separating must-haves from nice-to-haves

Here’s how they do it.

#1: They start with the riskiest assumption

Teams zoom in on the ONE SINGLE assumption that could sink the entire product if it proves false.

The thing that, if wrong, makes the product irrelevant. They design the MVP to answer that single, existential question.

For example:

If charging money is core to the model, the MVP must expose a real payment screen so users can actually enter a credit-card number

If the value proposition depends on replacing Excel, the MVP must enable users to import or recreate a live spreadsheet workflow

#2: They use a hypothesis statement

A clear hypothesis statement transforms MVP aspirations into a testable experiment.

Here’s one, for example:

“We believe that [persona] will [benefit] with [feature]. We’ll know this is true when [metric].”By pinning down the target user (persona), the promised value (benefit), the mechanism (feature), and the success signal (metric), the team aligns on exactly what must be true for the idea to succeed.

Everyone can now see what has to happen, for whom, and how success is measured.

“If X% of users complete Y within Z days, we proceed.”

#3: They slice an End-to-End thin vertical increment

A thin, vertical slice is one that touches every layer, i.e. UI, API, data store, and ops, yet handles only the single workflow that proves the hypothesis.

The user journey can’t stop at a mock-up or demo, as in the case of a Prototype. It must cover every link in the value chain, however thinly.

For example, the MVP user journey must help the end user do the following:

Discovery: The target user can actually find the solution (ad, search result, email, QR-code, etc.)

Try: In just a few clicks, they access the core functionality and can operate it independently

Get value: A real problem is solved or a tangible benefit is delivered (e.g. file successfully shared, order placed, etc.)

(Optionally) Pay: If monetization is part of the hypothesis, users must have a frictionless way to make a payment or commitment

Receive confirmation: Immediate feedback that the action was successful, including receipt, a success screen, delivered output, and a thank-you email. This closes the loop and lets the team measure retention or repeat use

Covering all of the above 5 steps, no matter how thin in a single “slice,” is what separates an MVP from a prototype.

#4: They timebox it to ≤ 1–3 sprints

Mature teams cap the MVP effort at one to three sprints.

This maintains a high level of urgency and prevents scope creep.

If the intended slice won’t fit that window, the team narrows functionality again, instead of relaxing standards like tests, security, and basic UX, which stay on the DoD checklist, while nice-to-haves get pushed out.

The 1-3 sprint constraint protects quality but ensures learning.

Taking the payment feature, for example:

Sprint length: 2 weeks.

Must fit: integrate Stripe Checkout for one-time payments, trigger an instant “Payment confirmed” response, and unlock the user’s booking immediately.

Won’t fit: coupon codes, multi-currency support, invoicing PDFs. Those move to the backlog instead of dropping tests, security, or reliability.

#5: They release to real users

Mature teams ship the slice to actual customers, but in a controlled way. For example, they:

hide the release behind a feature flag,

invite a small pilot group to test, or

expose the release only in a sandbox workspace

This maintains a low blast radius while ensuring the feedback remains genuine.

Which feedback?

Feedback, such as activation rate and task completion, etc.

#6: They use the feedback and make a decision

After the data (feedback) comes in, mature teams use a pre-planned decision gate to make one of the following decisions:

Persevere: If metrics are met, then double down on the feature

Pivot: If the core need is confirmed but the current solution falls short, then change direction

Kill: If the assumption is invalidated, free up capacity for the next hypothesis

This decision-making is the primary reason the MVP is built.

Takeaway

If your team wants to ship a successful MVP, then start with the following question:

“What’s the smallest experiment that will give us confidence to invest more or pivot?”

Don’t ask:

“How can we ship faster and cheaper?”

Those are very different questions with very different answers.

An MVP that nobody uses because it’s too half-baked teaches you nothing except that you wasted time building something non-viable.

That’s actually the most expensive outcome of all.

Show your support

Every post on Winning Strategy takes ~ 3 days of research and 1 full day of writing. You can show your support with small gestures.

Liked this post? Make sure to 💙 click the like button.

Feedback or addition? Make sure to 💬 comment.

Know someone who would find this helpful? Make sure to recommend it.

I strongly recommend that you download and use the Substack app. This will allow you to access our community chat, where you can get your questions answered and your doubts cleared promptly.

Further Reading

Connect With Me

Winning Strategy provides insights from my experiences at Twitter, Amazon, and my current role as an Executive Product Coach at one of North America’s largest banks.