Why Does Your Team Feel Busy But Deliver Nothing?

Why adding more developers usually makes everything slower?

Marcus (an old friend) runs engineering at a Series B startup you’ve probably heard of. Smart guy. Former Google, Stanford MBA, the whole thing. Three months ago, he called me at 11 PM on a Tuesday.

“We’re failing every sprint,” he said. “Every single one. And my team is working nights and weekends.”

I’ve known Marcus for about five years. This wasn’t normal for him. He doesn’t panic.

“Tell me what’s happening.”

Marcus walked me through it. His team of eight had committed to 40 story points for the sprint. Reasonable number, he thought. They'd done 35 the previous sprint, and he'd hired another developer.

Two weeks later, they delivered 12 points. Half the work sat in testing. The other half wasn’t even finished. Stakeholders are furious. The team is exhausted.

“So we did a retro,” Marcus said. “Everyone agreed to work harder. We committed to 40 points again.”

I already knew how this ended.

Next sprint: 15 points delivered. Same pile-up in testing. Same exhaustion. Same fury.

“Marcus,” I said. “How many hours a day do you think your developers actually write code?”

Silence.

“Eight hours, right? That’s what we’re paying them for.”

I’d heard this before. I hear it constantly. And it’s the first place everything falls apart.

I brought in Satya…

Satya is a Delivery Lead I've worked with for years. She's helped rescue probably two dozen teams like Marcus's. When I explained the situation to her, she laughed.

“Let me guess,” she said. “He’s planning like people work eight hours a day on sprint work.”

“How’d you know?”

“Because everyone does. And they destroy their teams!”

Satya agreed to audit Marcus’s team for a week. What she found wasn’t surprising to her, but it shocked Marcus.

His developers spent their days like this:

45 minutes in standup and other events

An hour in “quick” meetings that appeared on their calendars

30 minutes on email and Slack

Another 30 minutes on administrative garbage—timesheets, expense reports, the performance review system that HR loved

15 minutes on bathroom breaks and grabbing coffee

And the rest? Maybe five hours. On a good day. When nobody interrupted them with “just a quick question.”

“Your eight-hour day is a myth,” Satya told him. “You’re planning for capacity that doesn’t exist.”

Marcus did the math. If his team had 5 actual working hours instead of 8, he’d been overcommitting by 60%. Every single sprint.

But this was just the start.

The Number that Marcus wasn’t ready for

Even after Marcus recalculated using realistic hours, the team still failed to meet the next sprint's goals.

Satya wasn’t surprised this time either.

“Who’s your tester?” she asked.

“Just one person. Jen. But she’s great.”

“How many points can she test in a sprint?”

Marcus pulled up his tracking. Jen had never validated more than 10 points in a sprint. Ever.

“OK, so your developers can build 30 points of work,” Satya said slowly. “But Jen can only test 10.”

The silence on that call lasted maybe 20 seconds.

“We’ve been building work that can’t possibly get tested,” Marcus said.

“Right. Your team’s capacity isn’t 30 points. It’s 10. You’re only as fast as your slowest essential function.”

I watched Marcus process this. He’d hired another developer, thinking it would speed things up. Instead, it just created a bigger pile-up at testing. Jen was drowning. The developers were frustrated that their work sat untested. And Marcus kept wondering why “adding resources” made everything worse.

He asked the question I’d been waiting for.

“How do I explain this to my CEO?”

The conversation nobody wants to have

Marcus’s CEO wanted dates. Firm commitments. “When will feature X be done?”

After the testing revelation, Marcus couldn’t give those answers anymore. Or rather, he could, but he’d been wrong every time, and everyone knew it.

“You can’t keep making promises,” Satya told him. “You have to start talking probabilities.”

Marcus hated this advice. I could hear it in his voice when he repeated it to me.

“My CEO doesn’t want probabilities. He wants dates.”

“Then he wants lies,” I said. “Because that’s what you’ve been giving him.”

That landed harder than I meant it to.

Here’s what Satya taught Marcus to say instead: “Based on our velocity over the last six sprints, there’s an 85% chance we’ll complete this feature by the end of Q2. There’s a 50% chance we’ll have it by mid-April.”

The first time Marcus tried this with his CEO, the response was immediate.

“That’s not good enough. I need a commitment.”

“Then we can commit to the end of Q2,” Marcus said. “But you should know there’s a 15% chance we’ll miss it. We’ve never been more certain than that about any deadline.”

His CEO stared at him. Then asked a question Marcus hadn’t expected.

“What would it take to get to 95% certainty?”

It was at this moment that they had a real conversation.

About tradeoffs

About what could be cut or delayed

About whether it was worth hiring a second tester

It was the first honest discussion of a roadmap they’d had in months.

But even with realistic capacity planning and probabilistic forecasting, Marcus still needed to see where the work was actually going.

Cumulative Flow

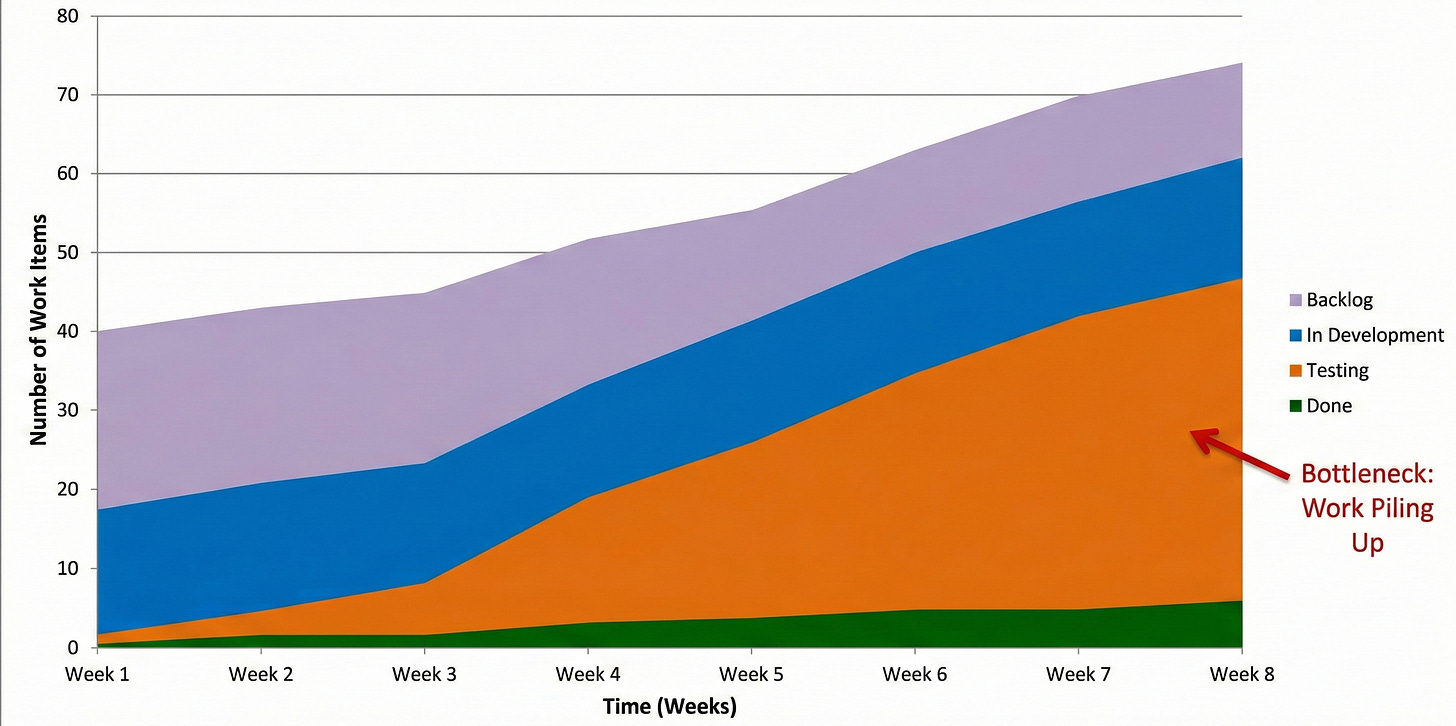

About six weeks into working with Satya, Marcus showed me something during one of our regular check-ins.

“Look at this,” he said, sharing his screen.

It was a chart with colored bands stacked on top of each other. The blue “In Testing” band kept getting wider and wider over time, like a snake that had swallowed something too large.

“This is a cumulative flow diagram,” he said. “Satya made me start tracking it.”

Now… I know what Cumulative Flow Charts are, but Marcus was looking at it like he’d discovered fire.

“You can literally watch the bottleneck happening in real-time,” he said. “Look… work enters testing here, but it barely leaves. It just piles up. This is why we kept failing sprints. It’s not that we weren’t working hard enough. The system was literally broken.”

The chart showed what Satya had told him weeks earlier. But seeing it visualized changed Marcus’s perspective.

“We showed this in our retro,” he continued. “Instead of everyone promising to work harder, we actually talked about the problem. We’re hiring a second tester. And we’re training two developers to do basic testing, so Jen isn’t the only one.”

That testing bottleneck had been strangling his team for six months. Six months of failed sprints and burnt out people. And the whole time, everyone thought the problem was effort.

The problem was never effort.

What Marcus's team looks like now

I talked to Marcus last week. His team has completed their last four sprints successfully. They’re delivering around 18 points per sprint now, less than half of what he used to commit to.

But they’re actually finishing what they commit to.

“Jim (his CEO) is happier than when we were promising 40 points and delivering 12,” Marcus said. “Turns out predictability beats optimism.”

His developers aren’t working weekends anymore. Jen isn’t drowning. And when Marcus gives a forecast now, stakeholders trust it.

He still struggles with the probabilistic language sometimes. His instinct is to give confident dates. But he’s learned that confident dates built on fantasy just create disasters you can predict.

Lesson for us?

Team’s capacity is not what we think it is…

What gets me about Marcus’s story is how common it is. I can’t tell you how many teams are right now planning sprints based on mythical 8-hour workdays, ignoring their bottlenecks, making promises they can’t keep, and wondering why they keep failing.

And the leaders running those teams… they’re not bad at their jobs. They’re just using a planning model that was broken from the start.

I know everyone’s going to say this is about tools and processes. Use the right estimation technique. Follow the events. Track the metrics.

But here’s what nobody wants to talk about.

The framework doesn’t work if leaders don’t actually want to hear the truth. Truth about capacity, what’s needed and what’s absolutely not needed.

The breakthrough in Marcus’s story wasn’t learning about cumulative flow diagrams. It was accepting that his team couldn’t do what he’d been asking them to do. That the capacity he wanted didn’t exist. That probabilistic forecasts were more honest than confident deadlines.

Most leaders don’t want to accept that. They want to believe that the right motivation or the right process will unlock more capacity. They want to believe that if the team just focused more or worked smarter, they could deliver those 40 points.

And as long as leaders believe that, the tools and frameworks are useless.

Satya put it well when I talked to her yesterday.

“Every team I rescue has the same problem,” she said. “Leadership planned for the team they wished they had, not the team that exists. And then they blamed the team when reality showed up.”

Marcus’s team is still the same people it was six months ago. Same skills. Same hours in the day. Same constraints.

The only thing that changed was that Marcus finally stopped planning for a team that didn’t exist.

Show your support

Every post on Winning Strategy takes a few days of research and 1 full day of writing. You can show your support with small gestures.

Liked this post? Make sure to 💙 click the like button.

Feedback or addition? Make sure to 💬 comment.

Know someone who would find this helpful? Make sure to recommend it.

I strongly advise that you download and use the Substack app. This will allow you to access our community chat, where you can get your questions answered and your doubts cleared promptly.

Further Reading

Connect With Me

Winning Strategy provides insights from my experiences at Twitter, Amazon, and my current role as an Executive Product Coach at one of North America’s largest banks.

Thank you for a story really brings the problem to life and breaking down the "mythical eight-hour workday." What really resonated was how teams who try to avoid the difficult conversation with leadership keep pushing forward and hoping for the best, but ultimately making the problem worse.

Fantastic breakdown! The testing bottleneck example is so relatable, I've seen similiar patterns where teams kept throwing engineers at a problem but never addressed the QA constraint. That line about being only as fast as the slowest essential function is gold and tends to get overlooked in capacity planning. We ended up doing something simlar last quarter and the CFD visualization made all the difference in getting leadership buy-in.